Halle Orchestra, Sir Mark Elder conductor. Germán Enrique Alcántara baritone | Simon Boccanegra; Eri Nakamura soprano | Amelia; Iván Ayón-Rivas tenor | Gabriele Adorno; William Thomas bass | Jacopo Fiesco; Sergio Vitale baritone | Paolo Albianil David Shipley bass | Pietro; Beth Moxon mezzo soprano | Amelia’s maid. Chorus of Opera North

Another Verdi opera I’ve never heard a note of before, let alone seen…..I think of the major mature operas it’s really only A Masked Ball, Macbeth and Luisa Miller that I will now not have seen, plus some early ones like Il Due Foscari. This was a collaboration between the Halle and Opera Rara, and is something I guess Sir Mark Elder wanted to do in his final year with the Halle. As you can see from the title this was a performance of the rarer 1857 original version, not the more commonly played 1881 one with dramatic reworkings by Boito – but as I have no knowledge of either version this didn’t really make much impact on me……….

On reflection after performance, this did seem to me to be a work which at least in its 1857 version needed a stage performance to have real impact. The characters seemed for the most part sketchily drawn and it’s not always easy to understand their motivations. Boccanegra for instance doesn’t seem a particularly tyrannical figure – he needs a director’s imagination to surround him with the ‘thugs’ and the “ informers’ who are mentioned in the text – it needed the apparatus of the surveillance state to make the point in a theatre. Likewise I found it difficult to understand what Fiesco was so upset about – after all his daughter, who is Boccanegra’s lover, dies unexpectedly but naturally, not as a result of anything SB does. Adorno seems a cardboard cut out Italian/tenor lover. Paolo is undoubtedly a Macchiavellian figure but nothing seems to happen to him at the end – he gets away with poisoning Boccanegra. Amelia alone seems more fully drawn as a character. Again, the number of male v female singers is striking – apart from Amelia’s maid, who only sings a few lines, Amelia is the only female singer. It makes for a long dark-hued and not fully engaging evening. A lot of the male parts are written in quite a declamatory style, and it’s only Amelia who really offers vocal fireworks during the work – similarly a lot of the music is slow, and there are too few exciting moments with chorus and orchestra at full throttle. There was little attempt during the performance to create any sort of staged interaction between the characters – Fiesco was notably stolid, and others peered at their scores a lot of the time; the only really engaging performances, in terms of stage presence, were by Boccanegra himself and Amelia, though Adorno did his best when not looking at the score. But I did enjoy some of the music – the end of Scene 2 of the Prelude, with (I think) the RLPO-owned bells making an appearance was notably thrilling; I liked too the finale of Act 1. At other times, it seemed as though a Verdi AI machine was at work, recycling melodies and their accompaniments that are heard to better effect in Traviata or Rigoletto. Sorry……

What I can say more affirmatively is that there was a lot of good singing around. Germán Enrique Alcántara was, I thought, absolutely outstanding as Boccanegra, with a beautiful golden voice, some lovely legato singing and sounding tremendously at home in the role – I would love to hear him sing Mozart (in fact he has sung the Mozart Almaviva at ROHCG). The Peruvian tenor Iván Ayón-Rivas sounded absolutely idiomatic as Adorno and sung very well. I was very taken by the sonority and depth of William Thomas’ bass voice – he’s clearly going places, though the actual nuancing of what he was singing could do with a bit more work: I wonder if he will be a Hagen or a King Marke in a few years’ time? The Amelia, Eri Nakamura, was good but perhaps less exceptional than some of the men – she dealt with but didn’t sparkle in the (not very many) moments of vocal fireworks; sometimes too her voice felt a bit small for the role, at least in a concert performance, and she had slightly too wide a vibrato at the beginning. The chorus sounded excellent and Mark Elder didn’t – as he had with Force of Destiny at ROHCG – seem to be taking too slow a pace at any point. The orchestra stumbled a bit at the very beginning but otherwise played very well – it’s interesting how Verdi at this point in his career was moving beyond the bel canto rum-ti-tum accompaniment to create more interesting orchestral sounds, particularly in the strings, which the orchestra and Elder brought out well.

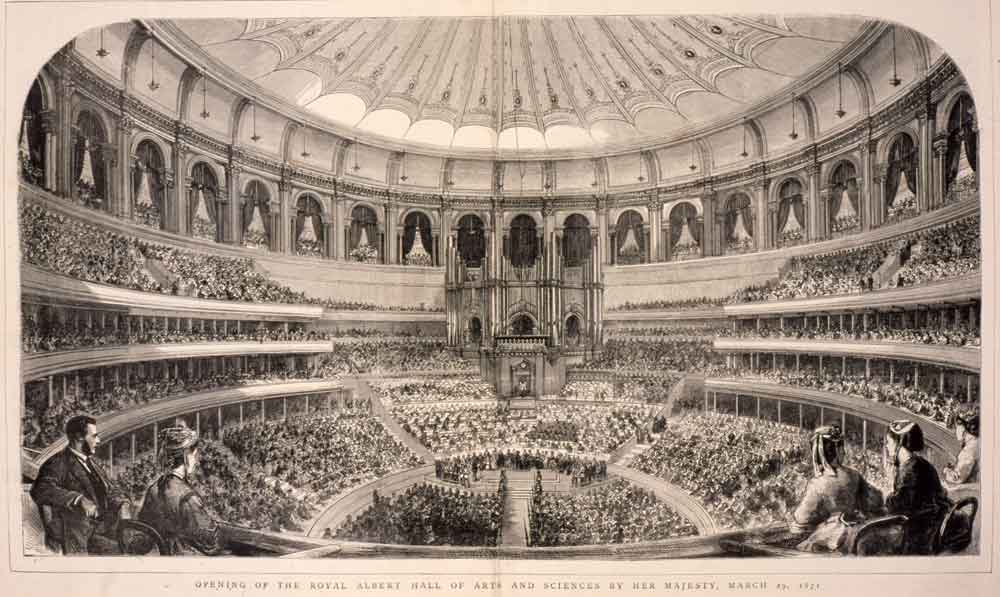

All in all, interesting but I am not sure I will be rushing to repeat the experience. It was interesting to see that the hall was pleasantly full, but certainly not sold out. How ENO can expect to run repeat performances of anything other than 4-5 popular operas (Carmen, Traviata, Butterfly) in Manchester I do not understand