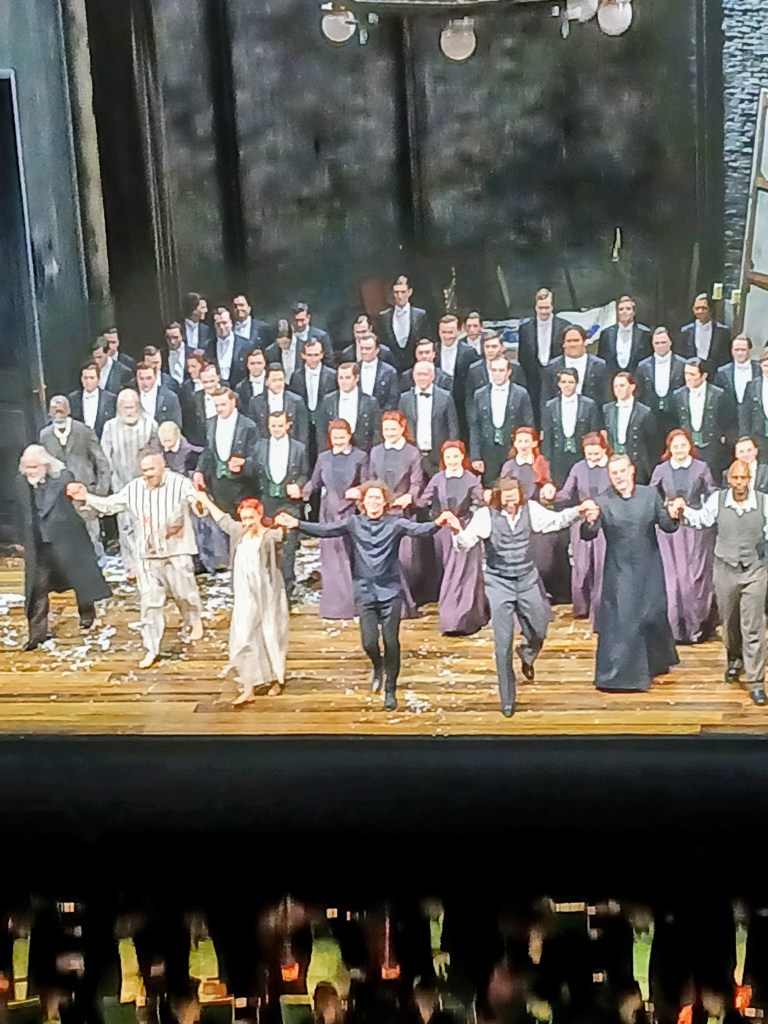

Paul Carey Jones, The Dutchman; Eleanor Dennis, Senta; Robert Winslade Anderson, Daland; Neal Cooper, Erik; Angharad Lyddon, Mary; Colin Judson, Steersman. Peter Selwyn, Conductor; Julia Burbach, Director; Naomi Dawson, Set Designer; Sussie Juhlin-Wallén, Costume Designer; Robert Price, Lighting Designer.

I haven’t been to the Holland Park Opera set-up since 2021 (when I saw excellent productions of L’Amico Fritz, The Cunning Little Vixen and Hansel and Gretel), and that was the first time then I’d been there. I remember enjoying the atmosphere and the way operas have to be performed there (in a tent, relaxed, little opportunity for fancy scene changes except in the interval, the uncertainty of noises off [peacocks and parakeets this time] and whether it will rain). It has what feels like a different crowd going to it from either Glyndebourne or the regular ROH/ENO-goers, and when the CEO of Opera Holland Park, in a welcome speech, asked ‘hands up those attending an opera for the first time?’, a surprising number of people put their hands up. Several people around me who had put their hands up were whooping enthusiastically after the performance, so it seems to have gone well for them. I tried to imagine hearing this work through their eyes and I could see it spoke to the mostly young couples who had put their hands up about the relationships between men and women, what love means, and so forth. Though some of the words (‘the duties of a woman to obey her father’) make me squirm, they didn’t seem so bothered

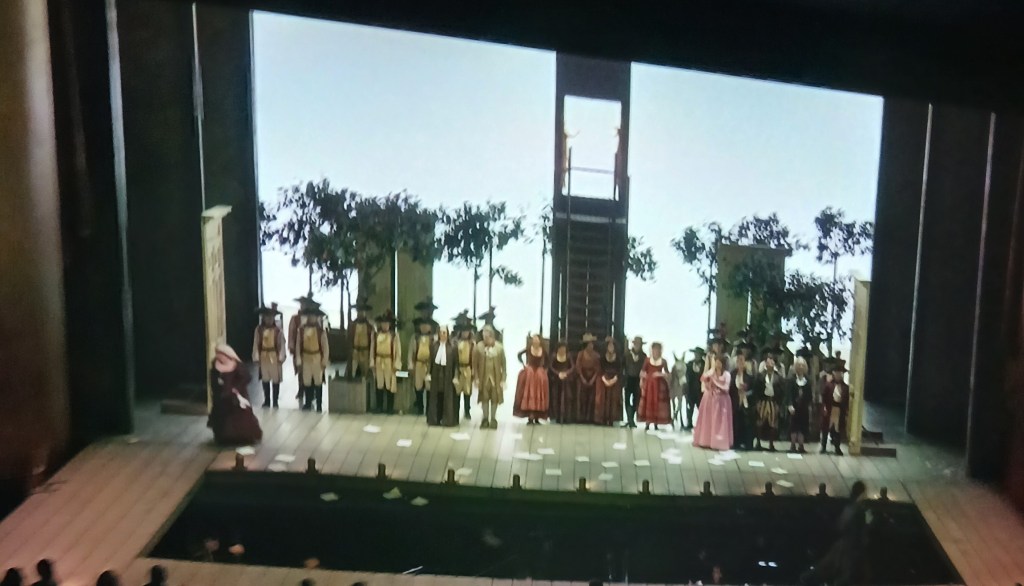

This was a straightforward production and performance of the Hollander which I enjoyed a lot. It focuses on Senta’s obsession and sheer oddness, and made the most of the specific theatrical context of Holland Park. The photos give you a particularly clear sense of the set and my memory is that all OH performances need to have the orchestra pit situated in the middle of the acting space, with a performance space behind and in front. As you can see, the area behind the pit is steeply raked, with the top representing Senta’s place of security and safety, with a bed and a lamp, and the bottom Daland’s table, but it is also used flexibly for the big choral scenes. The area in front of the orchestra is a gravelled space representing the sea shore (and other places) and is where the picture of the Dutchman is held – under a bollard or something similar. The two big staircases into the auditorium are often used by the chorus for exits and entrances – they run in and out, adding to the energy of the production. The tent area conveniently does for a general sense of sails, and then there are ladders and ropes around as well to add to the ship-like impression. Costumes are broadly modern and all colours are muted – grey, browns, dark green and black – with the exception of Senta, who is in white or wine red. As you can see, the set is very busy, and the one drawback of it – but maybe this was intentional – is that it was sometimes quite difficult to know when the Dutchman was entering, in his all-black coat. Given the complexity of the stage area here, and extra things to take into account like the steep raking of the back stage, direction of movement was generally good, but there were one or two moments when things seem to droop back into stock operatic acting – semaphore arms and face the audience, particularly with poor old Erik, a thankless part if ever there was one. There were appropriate sound effects and occasionally the whistling of wind which came from the outside. The ghost ship was suggested by flashing lights and a fairly abstract projection.

Wagner made a range of revisions to the work throughout his life and this one had a few seconds of music I don’t recall hearing before (maybe the recent ROHCG production used them). This OH production employed the early 3 act version, with an interval after the first act, and the version which does not have the ‘redemption’ theme at the end of the overture and the conclusion of Act 3 (as with ROH). This makes for a less than wholly satisfactory ending – Senta has the spotlight on her, sings her final words about eternal fidelity and then slowly walks off up one of the staircases. It is unclear what her fate is – a problem in the production but also arising from how Wagner ends this version.

Peter Selwyn conducted the work broadly but without ever losing momentum, and with plenty of energy for the Dutchman music and the sailors’ songs. I was very impressed by the orchestra – the City of London Sinfonia – which is obviously a reduced one, given the size of the pit and the need to keep costs down, but which had all the volume, detail and bite you need in this score. The horns and trombones sounded particularly splendid, but the string sound was warm and never sounded thin or scratchy. And a shout to the timpani player, who was thwacking away enthusiastically. And, to my ears anyway, there were very few mishaps and wrong entries.

The cast was very strong. As in so many other productions in the UK over the past few years, I am constantly coming across British singers I’ve never heard of before – Eleanor Dennis I thought was very good indeed. She’s tall and able to be still and yet have a significant stage presence and used those qualities to help portray the depth of Senta’s obsession. Her voice was powerful, top notes secure and with plenty of shading – she had all you want for an ideal Senta. I was reading an article about Lise Davidsen’s recent recording of this work where the reviewer refers to the fact that Senta as a role is deadly for singers’ vocal chords, and Davidsen herself has said she would never sing the role again after the recording and the concert performances in Norway. I hope Ms Dennis’ voice survives these performances…….I was also deeply impressed by Paul Carey-Jones, who I had previously come across as a fine Wanderer at Longborough during their recent Ring. He has all the gravitas you need for a good Dutchman – again, confident stage presence, a strong but warm voice easily spreading throughout the whole auditorium, and excellent diction. His approach at the beginning of Die Frist ist Um and the Act 2 duet was inward, beautifully legato – drawing you in superbly. Robert Winslade Anderson’s Daland was a lighter, rather dry, – voiced character than you get sometimes, but conveyed well his venality and was confident on stage. Colin Judson and Angharad Lyddon did their best with Erik and Mary. The chorus sounded tremendous, and they were extremely well directed !

As I walked back towards Holland Park tube station I found myself in reactionary mode, feeling perhaps newly and freshly outraged by the Tcherniakov Bayreuth Dutchman I saw in 2022. If a publisher decided to publish a book under the title of Pride and Prejudice which took the view that Jane Austen needed expurgating and updating to reflect contemporary views, and twisted round all elements of the plot in the process into a new story, there would be outrage from all quarters if that were then published as ‘by Jane Austen’. Why is the critical framework for that Bayreuth production any different? OK, there are elements in the text which are outdated – particularly concepts of daughterly obedience- but any competent director can find a way of handling these (eg suggesting Daland is abusive). And, yes. I know about modern theories of theatre, and observers recreating the text, but still – it has to be understood as a shared experience, with understand being emphasised. As for concepts of eternal love – well, these have been around in at least the 3 main monotheistic religions for thousands of years…….And for the sake of the future of the art form any director should always be thinking- what would anyone who hadn’t seen/heard this work before make of my production? Barrie Kosky’s recent Walkure shows how a director can handle a canonic work brilliantly, offering new insights without in any way distorting what is going on, and all the while remaining faithful to Wagner.