Conductor, Christian Thielemann; Production: Jan Philipp Gloger; Design, Ben Baur; Costumes: Justina Klimczyk; Lighting: Tobias Krauß; Video: Leonard Wölfl; Choreography: Florian Hurler; Sir Morosus: Peter Rose; His housekeeper, Iris Vermillion; Barber Cutting Beard: Samuel Hasselhorn; Henry Morosus: Siyabonga Maqungo; Aminta, his wife: Brenda Rae; Isotta: Evelin Novak; Carlotta: Rebecka Wallroth; Morbio: Dionysios Avgerinos; Vanuzzi: Manuel Winckhler; Farfallo: Friedrich Hamel

After the usual problems with Deutsche Bahn, I arrived in Berlin from London an hour and a half later than scheduled in the evening but still with enough time to go to my hotel via the S Bahn and have dinner locally in Kurfürstendamm.The next day I had an interesting morning at the German History Museum and then a good lunch near Unter den Linden. After a drink and a rest, on to the Staatsoper for the first of four operas I am seeing during this trip

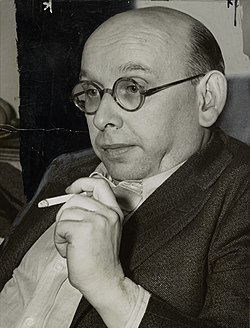

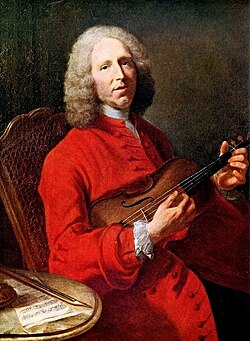

Die Schweigsame Frau is a fairly late Strauss opera (premiere 1935) and Hofmannsthal was dead by the end of the 1920’s. Strauss’ replacement librettist for this adaptation of Ben Jonson’s Epicoene was Stefan Zweig, the eminent Jewish Austrian writer. The work had a troubled early history – a year before the opera opened in 1935, Zweig fled his home in Austria for London, as a result of threats. After the premiere, Die Schweigsame Frau was quickly banned by the Nazi Party because of Zweig’s involvement in the work, and Strauss was forced out of his post as president of the Reich Music Chamber. Even in Germany the work is still not performed that often, and in the UK it has not been heard since 2003 at Garsington (the ROHCG presented the work in English at the UK premiere in 1961 and the opera formed part of the Glyndebourne festival in 1977 and 1979).

The plot involves an old man longing for company but who is enraged by bustle and noise. When a much loved nephew, Henry, reveals that he and his wife Aminta have taken up with a troupe of performers, the man, Sir Morosus, disinherits him and vows to marry immediately. The nephew, Henry, responds with an elaborate prank, organising his troupe into a group of ‘silent women’ who will be good submissive brides for Morosus to choose from, and tricking Morosus into a fake wedding with one of them, his wife Aminta. The charade is played out, though Aminta feels quite fond of Sir Morosus and wishes she hadn’t agreed to deceive him. Nevertheless she becomes Morosus’ fake wife and turns into a nag, constantly scolding him loudly. Eventually Henry and Aminta own up to the trick after causing almost a nervous breakdown in Morosus, and the work ends in reconciliation between Sir Morosus and Henry, once again his heir, and a reconciliation in broader terms between the old man and the world – he has become more tolerant of others and more accepting of his situation in life. If the plot seems vaguely familiar that’s because the librettists for Donizetti’s Don Pasquale also used the Ben Jonson play for that work.

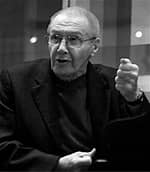

There are three firsts involved in this new production – it’s Thielemann’s first time conducting a new production since his taking over at the Staaatsoper; it’s also the first time he has conducted this piece, and, amazingly, despite the fact that Strauss worked regularly there for 20 years and led over a thousand performances for the theatre, it’s the first time the work has been performed at the Staatsoper.

The piece is not easy to stage, although the layers of complexity in a way help. One is left wincing in the first act as Morosus enthuses about the idea of ‘quiet women’ who do what they are told by men, and the text then portrays them as nagging all the time, and being too calculatingly enthused by the idea of a rich husband – all of which is how Morosus thinks, at any rate, but it is also true that Aminta and the theatrical troupe show a different much more assertive version of how women behave. Some of the more wince-able sessions are in fact when Aminta and the troupe are acting in front of Morosus, fulfilling his myogynistic expectations. Less easy to understand is how either Strauss or Zweig found this work’s essential focus relevant to the urgency of the time it was written, though I suppose the emphasis on a created community is there in the work, which is some sort of retort to the NSDAP notion of the volk. Still, at least we didn’t have SS officers or brownshirts making an appearance in this production (cf Arabella in my review earlier this year and Capriccio in Munich in 2022). The director Jan Philipp Gloger has chosen a contemporary Berlin setting for the work and says it is about older people’s loneliness, mysogyny and the housing problems of big cities. The latter I don’t really buy, although the overture to the work has housing ads coming up on the front curtain – I really don’t see this as relevant. Morosus’ house is plenty big enough! The other two themes though do run through the work. I felt the director and designer had got things absolutely right – there was no heavy emphasis to make a particular point, but just a very effective telling of the story and encouraging everyone on stage to think through their parts clearly. There are though some crowd scenes and also dance routines for Henry’s acting troupe which need a clear directorial hand, and these worked really well.

The set was made up of 3 rooms and an additional hallway which could be moved left or right, to give plenty of room for plotting/additional acting, The work is long, and I suspect Thielemann performed it without cuts (I’d say 3 hours at least). Having two intervals made it longer…..). There are moments when things drag – particularly in Act 3 as the net of the deception closes in (Rosenkavalier has the same longueurs at this point) but, although this is not top-shelf Strauss, I was impressed at the number of musical highlights. For instance:

- The paean of praise to quietness and peace which Morosus sings in Act 1, the declaration of love between Henry and Aminta and the final chorus also of Act 1 are all super pieces of music

- In Act 2 it’s the closing duet between Henry and Aminta which has the most impact, made more poignant by Morosus’ request that Henry guard his door while sleeping to prevent the un-quiet woman getting in….But Aminta’s first presentation of herself is also very touching – even if totally faked – while her expressions of self- disgust at what she is doing is movingly expressed.

- In Act 3, Morosus’ final words – I read somewhere that this is often sung in recitals – about finding a new sort of quietness and being an accepted part of the community he has come to know – the players – which has given him a happiness he’s never had before and quite removed his old grumpiness are really terribly moving – I found myself identifying with Morosus’ former self at that point!! This is 5 star Strauss.

I loved the company feel of the production, and how well it had clearly been rehearsed, But nevertheless there are some roles who stood out.

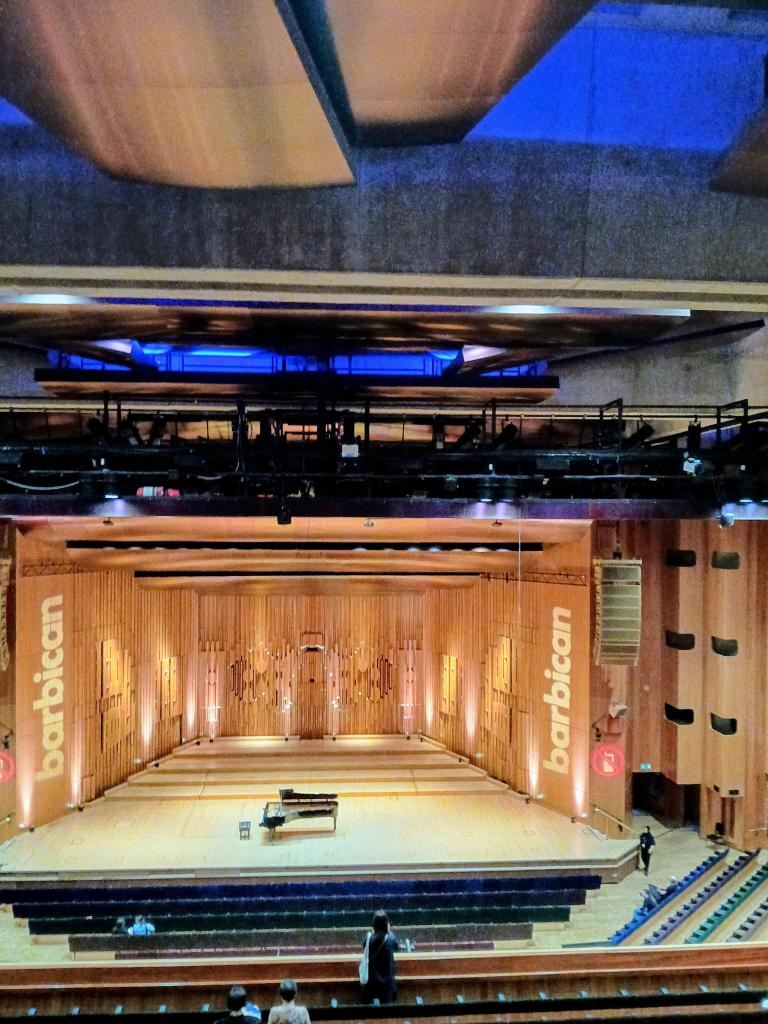

- Peter Rose is someone who is seen more often in Europe than the UK, though I heard him in May at the Barbican as Mr Broucek. His Morosus was quite outstanding – well-acted throughout, both the grumpy and the gentle side of Morosus’ character being well portrayed, and he has a beautiful bass baritone voice which conveyed particularly well the reconciliations at the end

- Brenda Rae, the American singer was also exceptionally good as Aminta , the role at its premiere taken by Maria Cebotari. This is a fiendishly difficult role – you have to be a very good actor, to have a lower register which can convey sympathy and warmth and also do some difficult coloratura runs. She did all this amazingly well

- The Barber and the Housekeeper are also significant roles, and these were well taken by Iris Vermillion and Samuel Hasselhorn

The orchestra as you would expect sounded wonderful – beautiful burnished horns, some lovely woodwind playing and deft strings. Thielemann, as I always find with him, graded the climaxes carefully, and achieved a clarity of sound that I would have thought would be difficult to achieve in this dense score

Director and the design team came on at the end, as is the wont with first nights. A few idiots booed them (I can’t imagine why) but they were roundly cheered by everyone else. Thielemann got the biggest ovation. This was a great evening experiencing a work for the first time which on the face of it I am unlikely ever to hear live again.