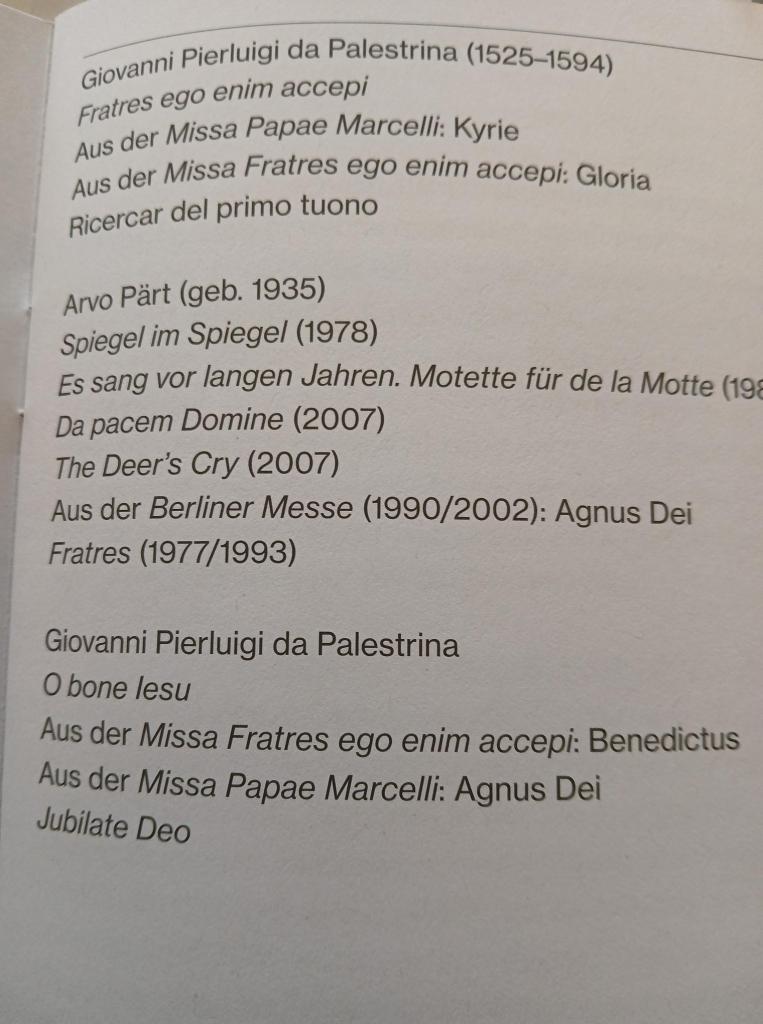

Arvo Pärt Cantus in memoriam Benjamin Britten; Dvořák Violin Concerto in A minor; Sibelius Symphony No. 2 in D major. Isabelle Faust violin, Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra, Andris Nelsons conductor

Again, not a totally obvious bit of programming, but I guess the common theme is new nations asserting themselves against dominant powers (Finland/Russia – Czechia/Austro-Hungarian Empire – Estonia/Soviet Union) with obvious contemporary reference. It was great to be hearing the Leipzigers again – I last heard them in 2023 powering their way through Mahler 8 – and also it was very good to see Andris Nelsons The last time I saw him – two years ago, Boston Symphony at the Proms – he looked grossly over-weight, he struggled onto the stage and his conducting seemed impeded by his weight. Tonight, he was half the size, thin and trim, and very active on the podium. He is either a very ill man (in which case I wish him a return to good health) or, much more likely, he has been on a very serious weight loss programme…..Unusually for me at the Proms, I was sitting in the centre of the Stalls, experiencing another aspect of the RAH’s quirky acoustics. At least the sound wasn’t unbalanced, though a bit echoey.

The Part piece is the kind of work well-suited to the hall – whispering violins slowly becoming audible from silence (beautifully played by the orchestra), brightly clanging bell, a swelling sound of string scales . The violins were split throughout the concert which here added to the richness of sound. It’s hard to imagine the work being better performed.

Isabelle Faust was a late replacement for Hilary Hahn. I’ve heard her a number of times in recent years and have always thought her a soloist who was a little cerebral and cool, with a beautiful, inward sort of sound. I wondered how she would sound in this concerto and in this hall…..the answer was that she sounded completely different from the last performance of hers I heard, the Brahms concerto. She gave a wonderful folksy lilt to the music, slightly accentuating some notes so that in the third movement her playing had an impetus that made you feel like dancing- and in fact an important aspect of her contribution was that she herself danced, swaying to the music in a folksy dress (and the Leipzig strings swinged in time with her!) . She was also able to project well the warmth, the beauty and melancholy of Dvorak’s first two movements (which maybe outstay their welcome a bit), with playing of great tenderness. Her playing was very clear and audible from where I was sitting, helped by Nelsons’ sensitive accompaniment, keeping the orchestral sound down to let Faust be heard fully (the final few bars showed what they could do when off the leash). The orchestra offered also some beautiful woodwind playing, the flutes outstanding. This must be one of the finest of the (not very many live) performances i have heard. Ms Faust played an encore, a Baroque piece by Nicola Matteis Jr, (Fantasia in A Minor )whose opening sounded curiously like one of the Dvorak melodies….). He was according to Wikipedia the earliest notable Italian Baroque violinist in London.

I realised as I prepared for the second half that I had never thought very much about Sibelius 2! I must have bought a recording of it when I was 14 or 15 (maybe Reiner and the Chicago Symphony), played it a lot, got to know it very well without really thinking much about why it was as it was, and how the different elements fitted in with one another – beyond vaguely summoning up images of tundra, pine forests and Finnish nationalism. Listening to it tonight, it was startling to hear how disjointed the first three movements were. The first movement throws around snatches of melody abruptly, with chasms of growing volume and silence. The second contrasts its solemn pilgrim-like trudging main theme with violent episodes and outbursts. The third movement contrasts manic activity with the time-stopping oboe melody. Even the triumphant ‘big tune’ of the finale has an alternating theme that suggests whirling wind-driven snow blowing everything off course. The whole work seems disturbed, fragmented, introspective. If there is a triumphant climax, that victory seems likely to be short-lived.

So I would want to hear a performance of this work which reflected its fragmentation and unsettling nature and didn’t make the ‘victory’ of the final bars more than provisional. I thought the first movement in this performance was very effective in that context – the intensity of the strings, the careful attention to dynamics, the wonderful brass playing near the opening were all supporting the unsettled nature of the music – as did some of the speed changes in the slow movement, alternating between faster than usual and very slow, with pregnant pauses, and some violent unsettled outbursts. These two movements had some superb woodwind and string playing, plus impressive solo trumpet playing of the ‘pilgrim’ theme. The third movement ‘tarantella’ was taken at a truly manic pace, with some beautiful woodwind and string playing in the ‘Trio’, and there was a flexible opening to the finale, with speedings up and slowing downs in the prelude to the ‘big tune’. Again, the ‘alternating theme’ was treated flexibly, gradually increasing in menace. Altogether I found this to be an unconventional reading but which very much conveyed the unsettling and provisional nature of the work. And as the finale moved to an end, the dynamics of the strings and brass were handled beautifully and they just made an utterly glorious sound, particularly the trumpets and timps…….I particularly appreciated the very careful handling of dynamics in the closing bars so that the end really did seem overwhelming – despite the reality of before and after………………..