City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra, conductor Robert Trevino : Gustav Mahler — Symphony No. 10 (arrangement by Deryck Cooke)

Mirga Gražinytė-Tyla was meant to be the conductor for this concert but she pulled out a week before the event – as she had been conducting in Rome a few days earlier on May 13 and was due to be conducting this in Birmingham around the same time, I’m not quite sure what was happening with her programming…..I’d not heard of the replacement but he is apparently a frequent visitor to Leipzig. It’s a pity not have heard Mirga conduct this work – I usually find her concerts inspirational.

I came to this concert with some trepidation. I can see why the CBSO were invited to the Festival – Nelsons used to be their chief conductor, Mirga was his successor, they have had a succession of winners as conductors that has given them a lot of kudos (Rattle, Oramo, Nelsons himself, Mirga) – but it’s still a bit of a leap from the three orchestras we’ve had so far to the CBSO. How would they fare?

The answer is….very well indeed. The CBSO is not the Concertgebouw, and no British orchestra in my experience (and I am happy to be told otherwise) apart from arguably the LSO has the kind of weight and thickness of string sound that the best central European orchestras have (and the Concertgebouw) – though the Halle are pretty stylish string-wise. But there were virtuoso performances from (particularly) the first trumpet (and his back-up in those searing long trumpet notes), and the first flute, and in general excellent tight ensemble. What the CBSO strings did have is a sort of acerbic lightness that goes very well with the sound world of this symphony. I was touched to hear someone next to me (I think – my German is minimal) say to his neighbour ‘They play like a German orchestra’. High praise indeed!!

I got to know this work through the first recording of the Cooke performing version – the Philadelphia/Ormandy recording. That was of Cooke 1, but in fact Deryck Cooke revised it another two times. It was interesting to hear some of the (minor but audible) changes he made, adding more texture and depth to the orchestral sound

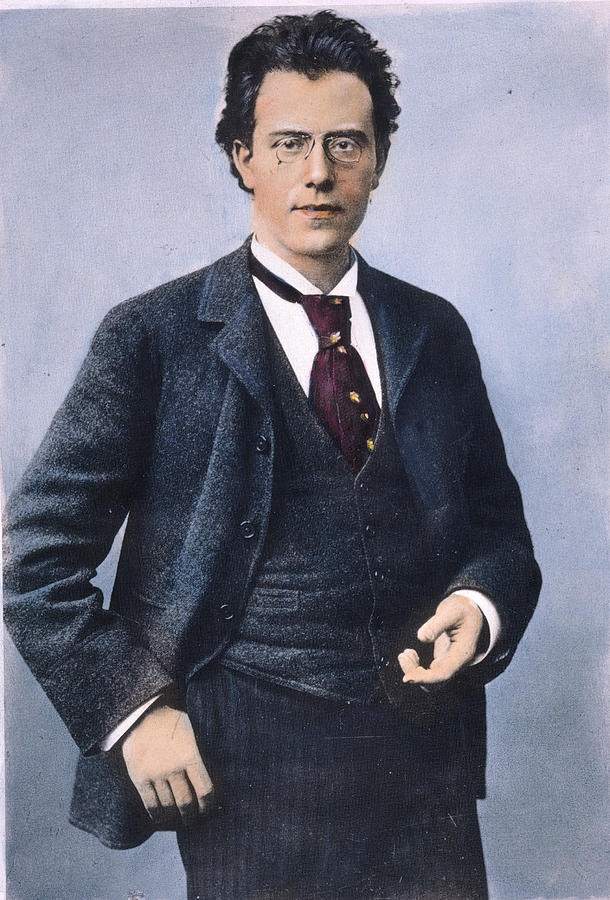

It is very easy to read Mahler’s life a little too smoothly into his works. As Stephen Johnson (who’s giving an English language lecture before each symphony in the Gewandhaus) mentioned, the enormous dissonant crash with the high trumpet in the first movement was added at a fairly late stage in Mahler’s development of the score, so it’s reasonable to assume that it is a response to the news of Alma’s infidelity in the Spring. But this work was being developed alongside the enormous triumph of the first performance of the 8th Symphony in the summer of 1910 in Munich, which established Mahler publicly as an eminent composer who was also a conductor, rather than vice-versa. Though he obviously knew of his heart problems, he had no idea at that point that he was going to be dead within a year. So while there is clearly an emotional journey in this work, it is not necessarily about a dying man, and may have (pure conjecture of course) more to do with his continuing grief for the death of his eldest daughter, and Alma’s adultery.

The symphony’s structure is much harder to ascertain than the first 7 symphonies, and it comes as no surprise that, according to Donald Mitchell, there is evidence that Mahler had some uncertainty about the order of the 5 movements as he developed the work. Essentially, we have a first movement that moves between consolation and bleakness, a second that is quite jolly, the deadly serious Purgatorio, the violent 4th movement and a final movement that brings back consolation to the fore. It is more difficult for a conductor and orchestra, therefore, to take us on a journey through this work which makes emotional sense than, say, the 5th Symphony. The best thing about this performance was that the journey was clear and made sense. Key elements were:

- The shattering climax of the first movement, which was brilliantly done, and overpowering in volume (the trumpet and high strings were extraordinary)

- The clarity and rhythmic impulse of the second movement

- The depth of the sudden upswelling of emotion half-way through the Purgatorio movement, which is, if not a break out moment to something ‘other’, then certainly the turning point of the work, where it’s recognised that the status quo, the continual grind, self-conscious jollity can’t continue, and that grim reality has to be faced and hopefully overcome

- The jagged edges of the 4th movement – though there were moments when the conductor I thought went too fast and, though the CBSO kept up with him, some clarity was lost in terms of note-value

- The beautiful way in which the consoling song of the last movement unfolded, and the passionate climax and upswelling at the end

So, all in all, a performance I appreciated very much of a work I haven’t heard very often live in the concert hall in the full performing version. One thing I noticed which I hadn’t before is the occasional influence of Parsifal on the score – Mahler didn’t, I think, conduct Parsifal in New York, taking the ban on complete performances outside Bayreuth seriously, but he did conduct extracts in New York and Germany. The opening of the first movement is very similar to the Act 3 Prelude, and at the end of the first movement there is a passage very similar to the closing bars of the Prelude to Act 1, as the curtain rises

What would have happened if Mahler had lived another 20 years – how might his work have developed? Stephen Johnson’s view was that the 10th symphony performing version suggests some very tentative answers – that he wouldn’t have tipped over into total atonality but, rather as Britten and Shostakovich did, used atonality within a fundamentally tonal perspective. But beyond that – who can say; how would WW1 have affected him? Would he have gone back to an impoverished and much reduced Vienna? Would he have been interned in the US? Sadly, we shall never know……..

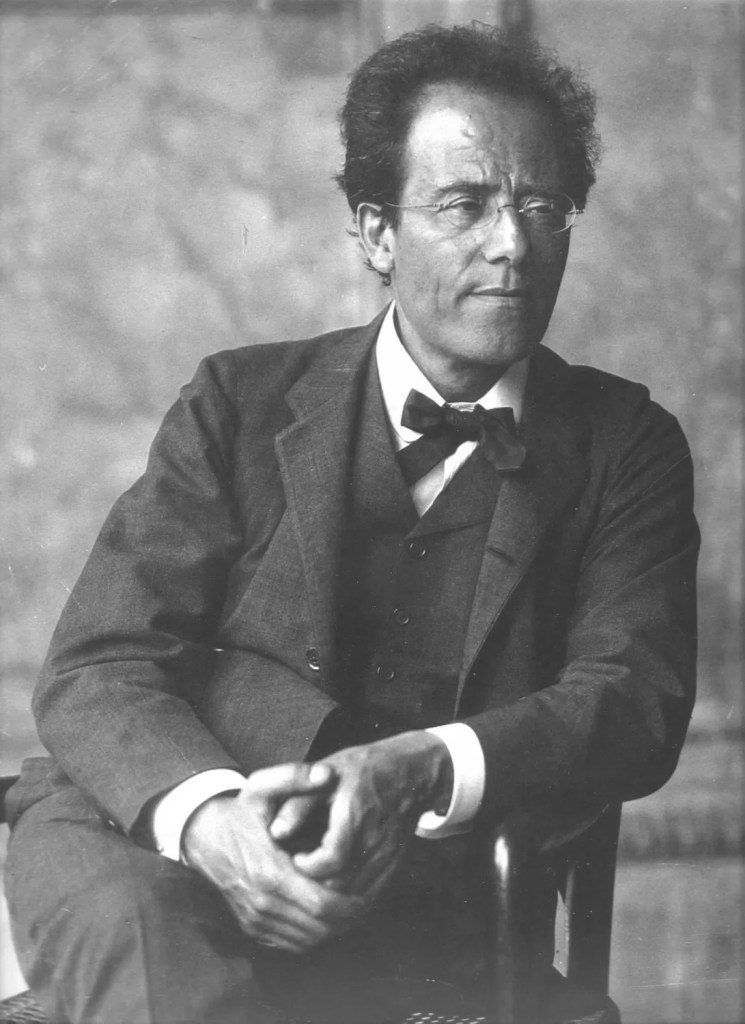

Mahler being carried off the train on his last journey, arriving in Vienna and reported by newspapers