Britten: Curlew River – A Parable for Church Performance, Op.71. Ian Bostridge tenor, Willard White baritone, Duncan Rook bass-baritone; Marcus Farnsworth., baritone Chorus of Britten Pears Young Artists, Deborah Warner director; Audrey Hyland music director; Christof Heter, designer.

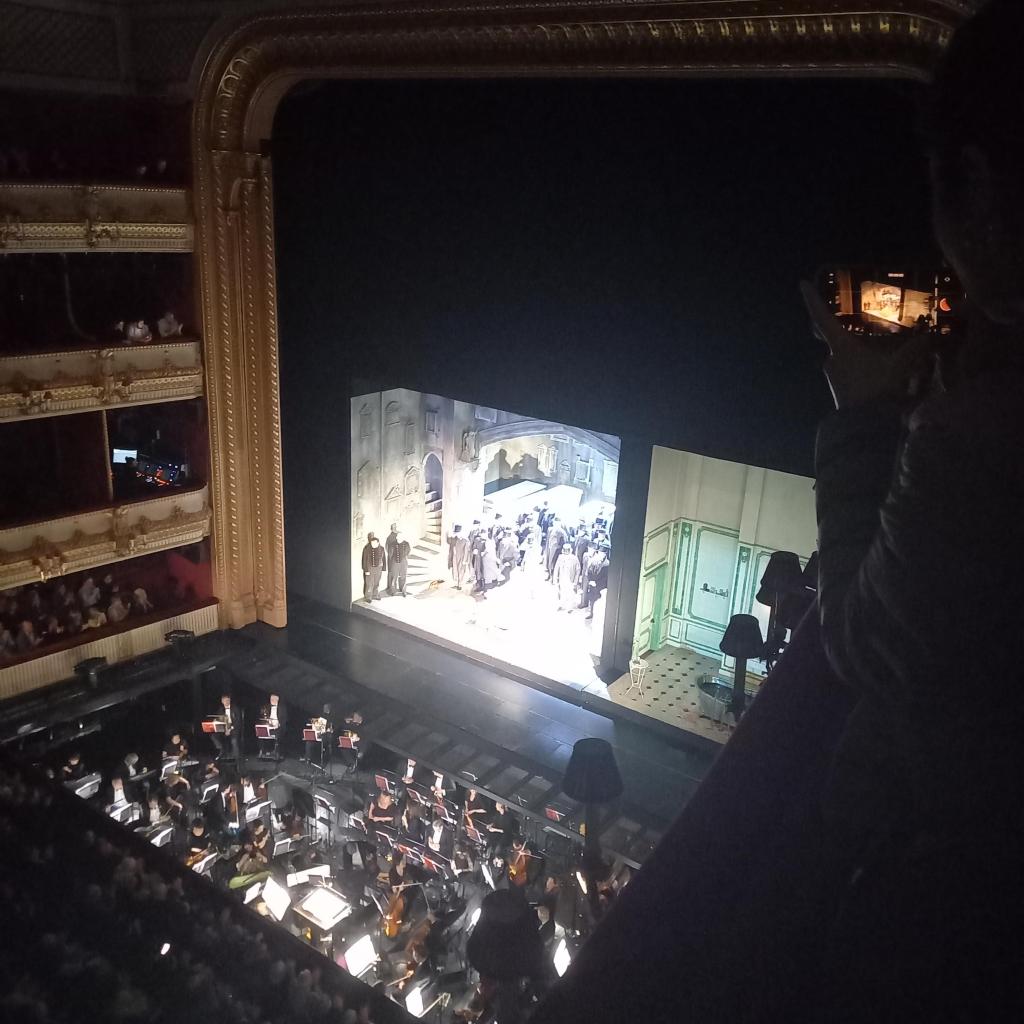

This was the first of two performances to mark the 60th birthday of the work, first seen in Orford Church in 1964. The wide space of Blythburgh church seemed equally suited to the work, and, in addition to its internal medieval features, particularly the carved angels, the fact that it is situated near a river and fens helps with the placing of the work in this church. The BBC was present at this performance to film it, hoping to show the work on TV in the Autumn.

The whole space of the church was used – singing actors entered by the south door and processed up the central aisle of the nave towards the chancel. There was a raised platform at the front of the chancel, facing towards the audience, but the aisle and indeed the western end of the nave near the font was also a performing area. In addition, a gradually ascending series of three rough planks started at the west end of the aisle, moving upwards to the chancel platform, and people acted and sang on this too. There was a sail that could be raised, hitched to the rood screen, a clever device.The music ensemble were over to the right as you looked at the stage, and from where I was sitting you couldn’t see them

I realised I hadn’t been thinking straight about how this work would be performed at one of the Aldeburgh Festival churches – I had assumed a darkened space and spotlights, but of course that is impossible to achieve in the middle of a sunny summer evening in a light and airy church, and so the performance was mainly lit by natural light, possibly aided by some artificial spots streaming through the west windows through a large BBC gantry positioned outside. There was some additional lighting for the chancel platform at points, particularly as the sun began to set.

Again, I had no programme notes with me, and though I’m aware of the connections with Noh plays, it seemed to ne the connections were not that clearcut. The use of male performers only, I assume is part of that, and of course there is a Japanese tinge to some of the music. But there are no masks, and no stylised movements – though I suppose the positioning of the musicians, and the slow movement of the story might also be aspects relevant to Noh. It is more the English medieval mystery plays that to me formed the background to the work – ordinary people coming on stage at the beginning in ordinary modern clothes singing plainchant and gradually changing to a different ‘workers’ smock, and setting up the stage, surrounded by the audience. The ferryman and traveller also looked vaguely medieval in their costume as did the Abbot and the monks/workers. The mad woman was more singularly dressed, coming on stage with a turned-inside-out umbrella and a yellow ball gown plus a man’s jacket, and clutching a thick quilt.

Deborah Warner has created a production that was entirely natural in movement, and there were no false steps. The coup de theatre of the clanging of the bell at the climax and the singing of the dead boy was beautifully realised and very moving. There was no imposition of a directorial vision at odds with the work. The only slightly controversial aspect of her direction was having one of the three boys involved in the singing walk down the central aisle after his voice has been heard because of the Mad Woman’s prayer, but that seemed to me perfectly legitimate .

I had been very much looking forward to going to see this, and I was not disappointed – this was a wonderful performance. There were, to my mind, several reasons for this:

- it’s more difficult to listen to this work just through an audio recording. Seeing as well as hearing it makes it come alive in an entirely new way. I heard music I had never really heard before – eg the swish of the oars, the bird song – because it is paralleled by actors’ movements and what’s happening on stage. I realised, listening to the Mad Woman, that the characteristic upward ending to her musical phrases is meant to echo the curlew’s song. Curiously diction on the whole was better in this live performance than on the Decca original recording.

- it was utterly riveting to be so close to great singers like Ian Bostridge and Willard White and see their consummate acting and see and hear their artistry – at times I was less than 5 feet away from them

- Ian Bostridge’s performance was quite remarkable. Obviously Pears has a unique status in this role, but it is difficult to imagine anyone else doing this better than Bostridge – he produced some beautiful singing that was very moving, and he acted with utter conviction, in a part which I can imagine others might exaggerate too much in. He did indeed throughout look haunted, with a distant look in his eyes.

- Hearing the work in this location was also important – you could feel, and almost see, the presence of the river and the fens beyond the stained glass windows

- Listening with concentration as you do in a live performance means you become immersed in the work’s sound world. It is utterly different to pieces written around the same time such as Midsummer Night’s Dream and the War Requiem, and yet you realise what a compelling and beautiful work it is. It makes me want to hear the other Church Parables, which I don’t know at all.