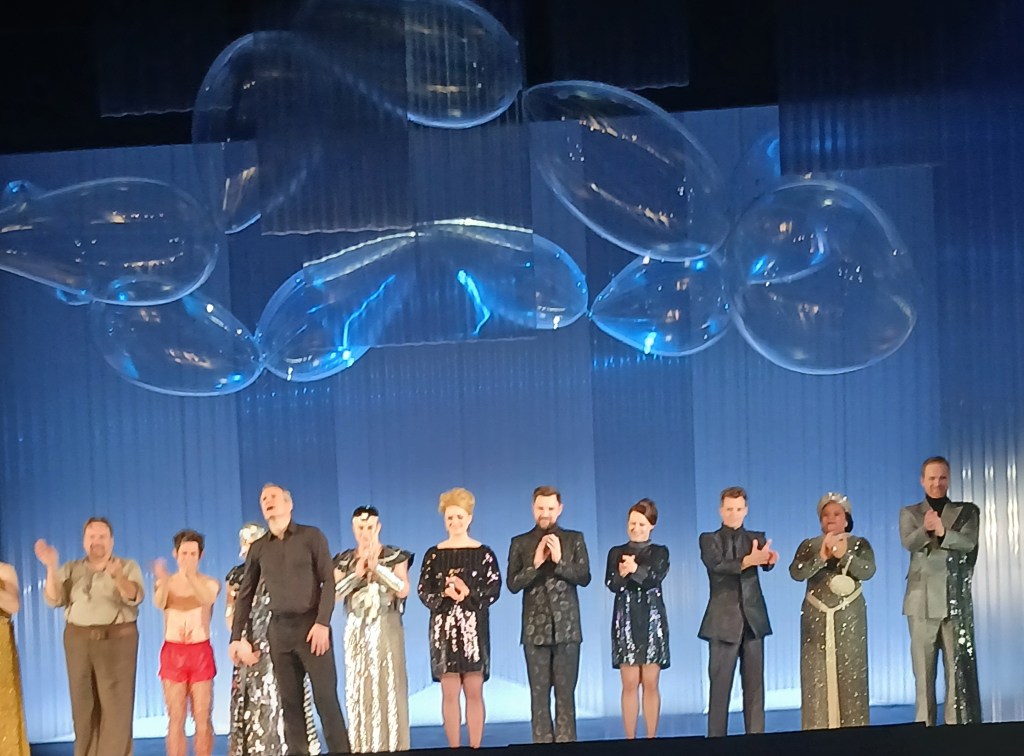

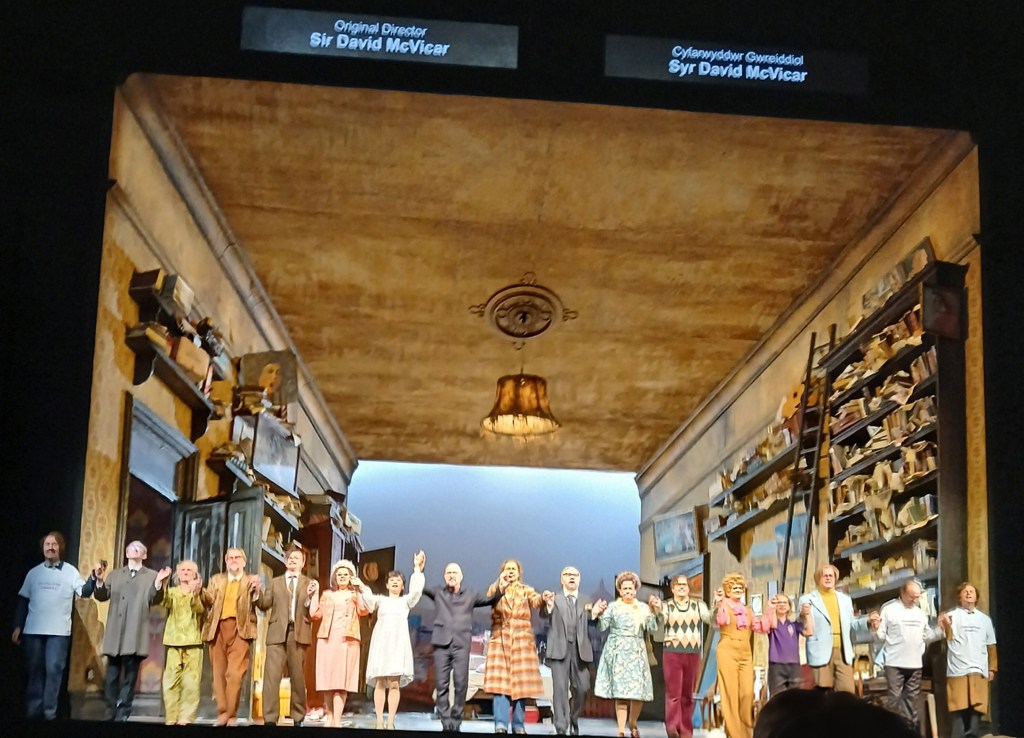

James Laing, Oberon; Daisy Brown, Tytania; Camilla Harris, Helena; Siân Griffiths, Hermia; Joel Williams, Lysander; James Newby, Demetrius; Henry Waddington, Bottom; Daniel Abelson, Puck; Nicholas Watts, Flute; Colin Judson, Snout; Dean Robinson, Quince; Andri Björn Róbertsson, Theseus; Molly Barker, Hippolyta. Garry Walker, Conductor; Matthew Eberhardt, Revival Director; Johan Engels, Set Designer; Ashley Martin-Davis, Costume Designer; Bruno Poet, Lighting Designer

The ON production has had some very good reviews, from Artsdesk and others. This was the third production I’ve seen of this work.

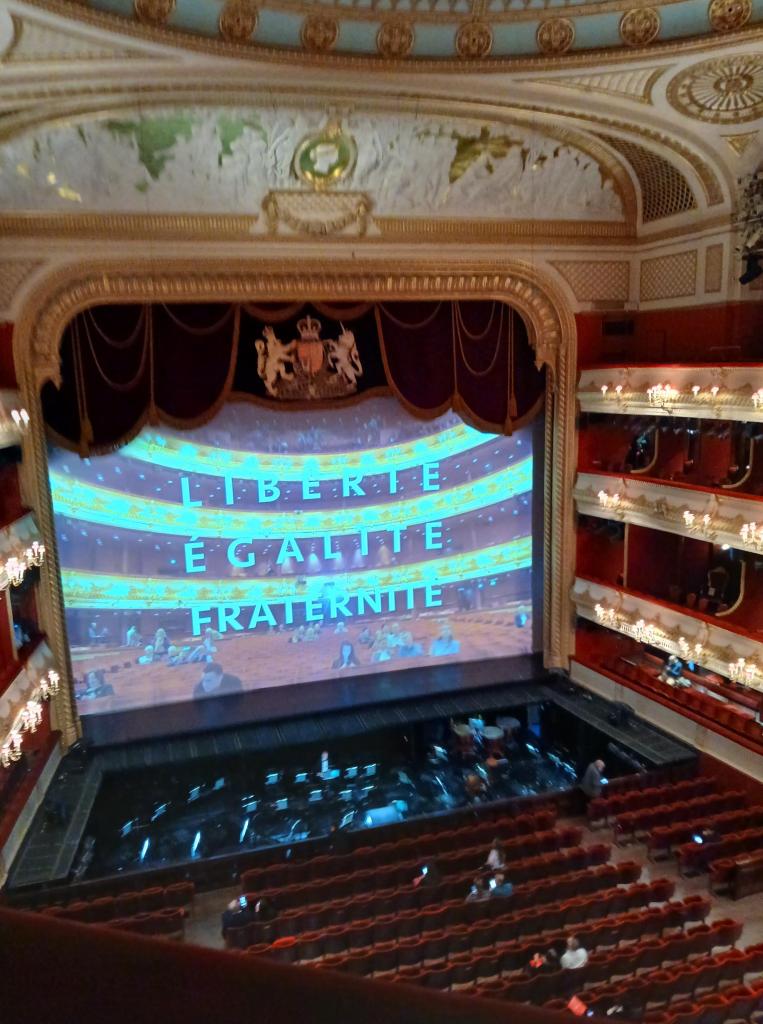

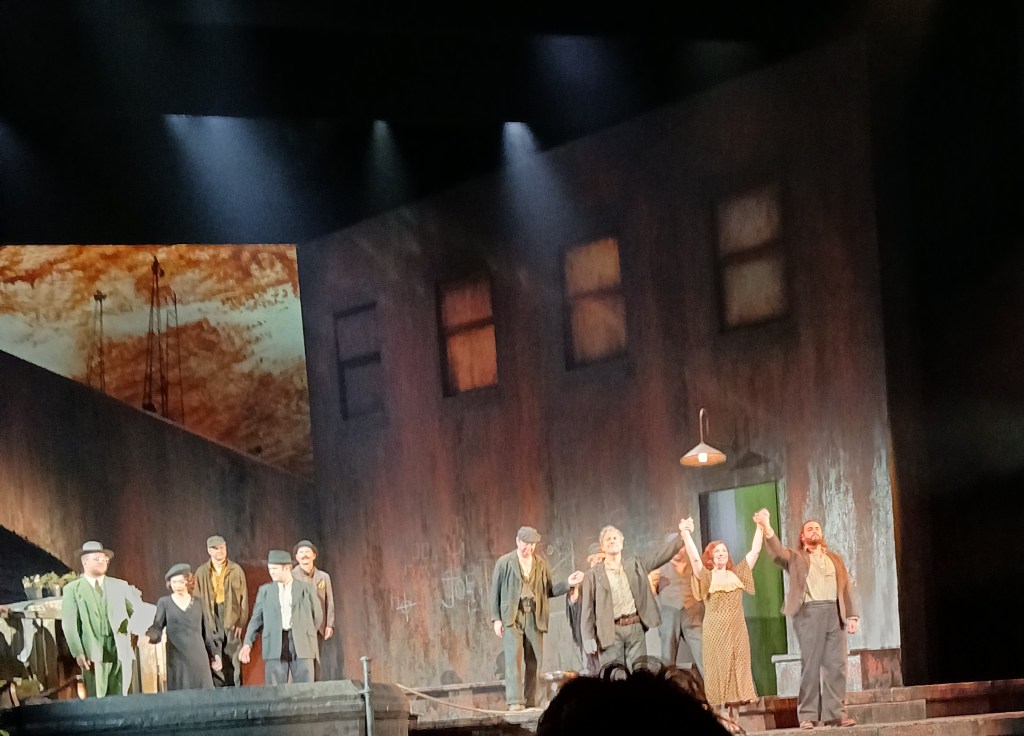

The Glyndebourne production, visually glorious, also had in its visual presentation shades of darkness in between the trees and the sunlight and therefore more of a sense of some of the less pleasant and more unsettling aspects of the work – the changeling boy, the cruelty and malice of Theseus and the savagery of Puck. The setting of the Opera North is meant to be the mid-late 60s – if you like, psychedelic – and this is certainly reflected in the clothes the four lovers wear and to some extent that of the ‘mechanicals’ as well, but it is not present in the basic set design which is as in the photos below – various floaty bubbles above the stage, and all around the sides and back silvery Perspex drapes, each with bunched edges at regular intervals, both hanging and floor-standing. Strips of plastic also move up and down to create different perspectives. The lighting is constantly the same silvery blue throughout with a few rows of not very bright coloured lights for scenes like Theseus’ palace. Occasionally with the aid of lighting effects there are shadows cast upon the screen, very effectively showing the silhouettes of e.g. the fairies. But interestingly while lighting created a very effective otherness in the forest – a place of new self-knowledge and rebirth – it offered no sense of the darkness of this work, something also emphasised by making the changeling child into a puppet and having a Theseus who, though he had his moments, was a bit of a pussy cat really. The fairies – boys and girls – were costumed in identical white T-shirts, shorts and socks, black wings and blonde wigs, and looked cute as opposed to anything else. Only Puck was truly unsettling – constantly on the move, shaking and nodding his head, crawling across the stage, shouting, and sneering. The Glyndebourne production was more fully rounded in showing all dimensions of this work. Where the ON production excelled was in the handling of the 4 lovers and Bottom & co. The lovers were well differentiated and individualised – much more so than at Glyndebourne. The ‘mechanicals’ were genuinely amusing – a matter of good timing, some effective gags (the costumes for the play were very good and funny, for instance – eg the Wall). Their antics were much appreciated by the audience and overall this aspect was better done than at Glyndebourne

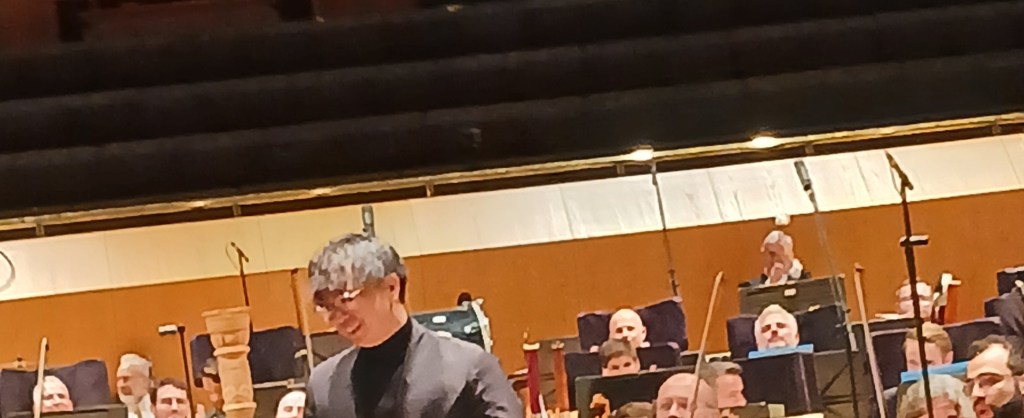

In terms of performers. the standout was Daisy Brown as Titania, who had a strong stage presence and a lovely voice – she floated a most gorgeous high note in her awakening solo. The four lovers were all strong singers, the most carefully differentiated of the group being the Hermia of Sian Griffiths. James Laing as Oberon was perhaps a little small of voice in this theatre and that added to a slight lack of impact in his performance, though that is to judge it at a very high level. The fairies were sometimes a bit hesitant of movement, though fine musically – I wondered if they recruit a different batch of singer fairies for each venue? Gary Walker kept everything moving and encouraged bright characterful playing from the orchestra. Given that there was only one basic set I was somewhat mystified by the apparent need for two intervals – the Glyndebourne production with more complicated set changes managed with one (though admittedly an hour long).

The audience was quite a reasonable one – more so than for some of the other ON shows I have seen in the Lowry. But nothing in the audience size suggested there was a massive number of people out there waiting to go to ENO shows in Manchester. The ENO Friends are having a session on 3 December when they are talking about who their partners will be and how things will work with their new life in Manchester – it will be fascinating to hear their plans…….