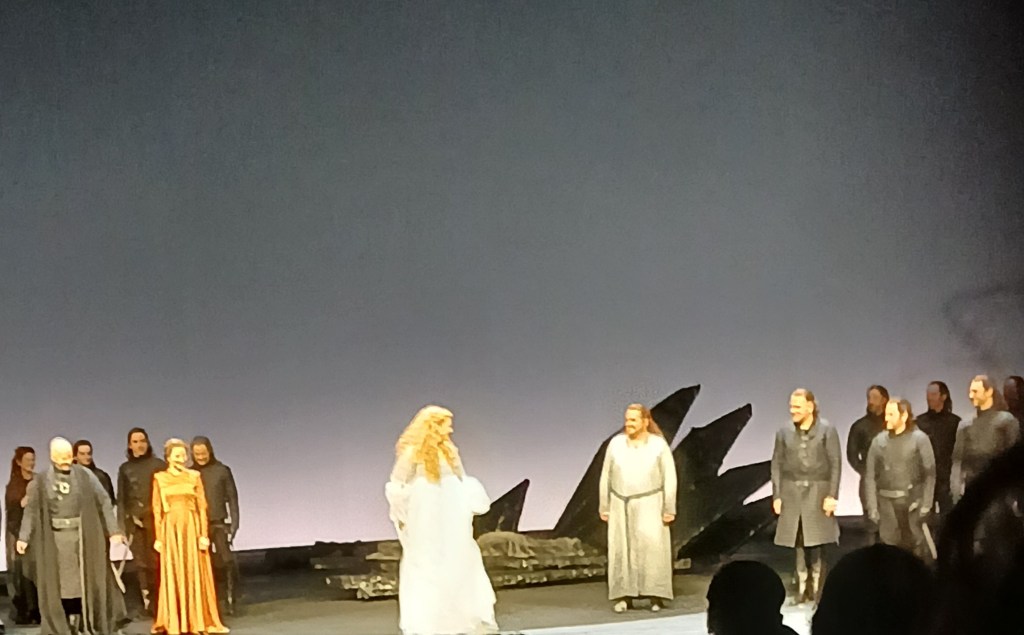

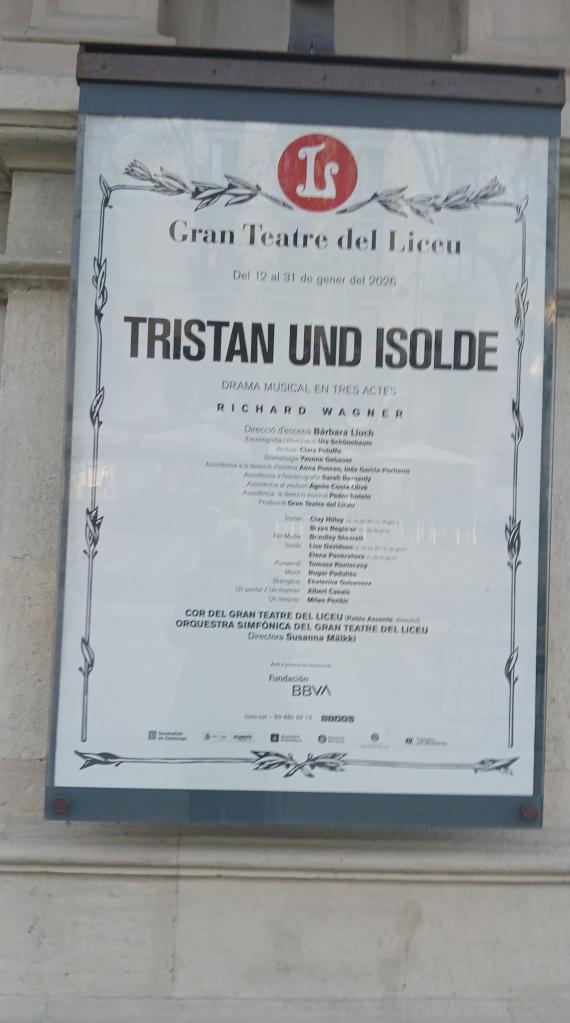

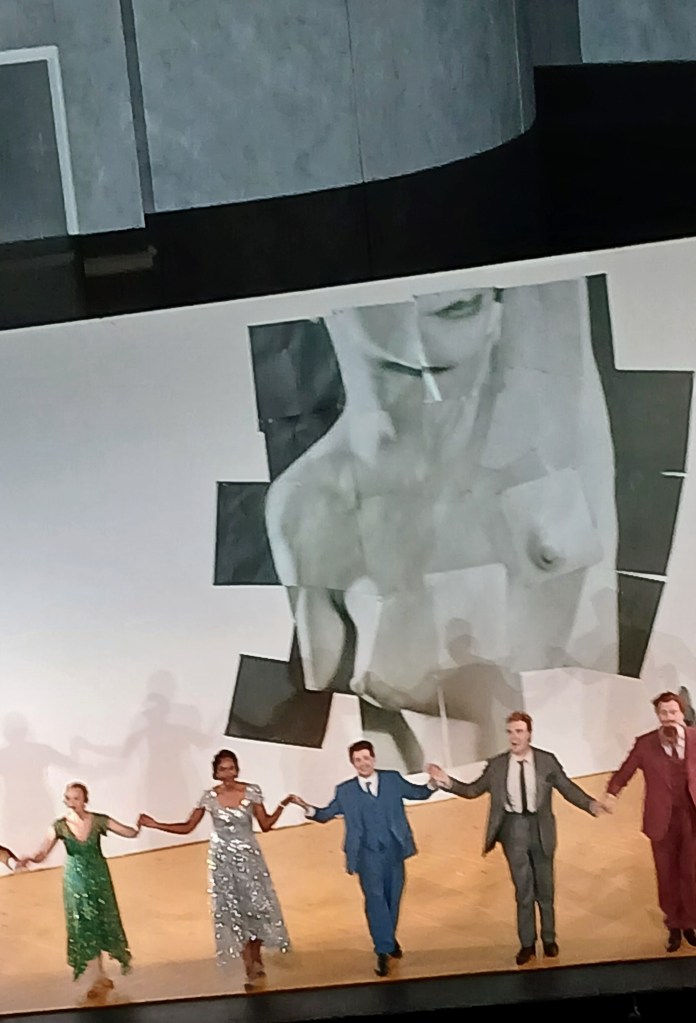

Clay Hilley, Tristan; Brindley Sherratt, King Marke; Isolde, Lise Davidsen;Tomasz Konieczny, Kurwenal; Melot, Roger Padullés; Brangäne, Ekaterina Gubanova; A shepherd / A sailor, Albert Casals; Milan Perišić, A helmsman. Director, Bárbara Lluch; Scenery and lighting, Urs Schönebaum; Costumes, Clara Peluffo; Conductor Susanna Mälkki

I spent a pleasant morning and early afternoon wandering around the centre of Barcelona, seeing the Gaudi-designed house Casa Batllo and having a very good tapas meal, with Eastern connotations, with an old friend also in Barcelona for Tristan,. After a quick rest, then, on to the Liceu Opera House. This has apparently been burnt down three times, the last in 1994 – but it has been finely restored to its original state. It’s a tall theatre (5 tiers) and with a stage that is certainly adequate but not enormous. I was sitting towards the back of the stalls, The sound was warm and resonant – the orchestra in particular sounding gorgeous, and the singers had no difficulty in cutting through the orchestra even at the loudest moments. So – a good theatre, I thought, and with less dampening of sound than Covent Garden.

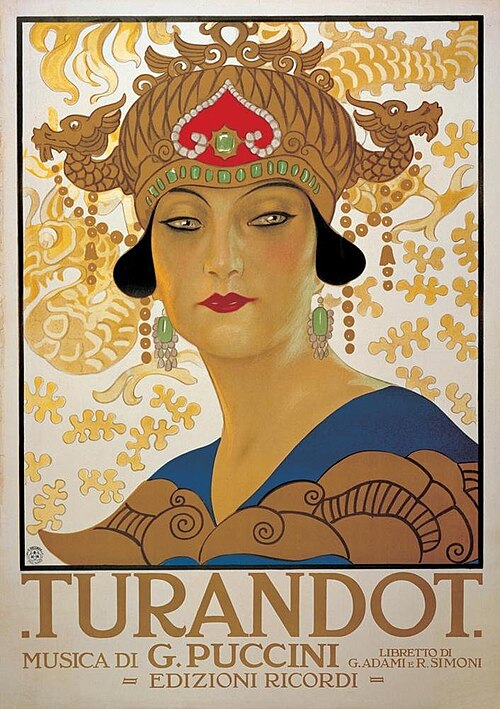

I have not seen that many performances of Tristan after the 1970’s. I heard two performances at Bayreuth in 2017 and 2024, both musically very good but, in the Bayreuth mode, without surtitles, and with questionable regie-theater interventions, and a Proms/Glyndebourne semi-staged performance in 2021. Because of the English surtitles, and because of the quality of the performance, this Barcelona production was probably the most gripping, engaging account of the work I have seen since those glory days in the 70’s (Kleiber at Bayreuth, Nilsson at ROHCG, and also Vickers).

Taking on the role of Isolde, and subsequently Brunnhilde, is something that many Wagnerians have hoped Lise Davidsen would agree to, and so there was an excited international component to the audience for this performance, of admirers of her singing from many different countries here in Barcelona both to support her and hear her sing the role for the first time. (January 12th was the first night of this run, so her debut in the role, though she has sung Act 2 in public with Simon Rattle before). All in all, it was an extremely fine performance which showed her to be in very good voice, her time off for child-birth having had no discernible impact on her characteristic sound, It was – above all – a thought-through performance, where the phrasing of every line seemed to have been considered afresh. She was commanding in the narrations of Act 1, with top notes securely pinged out, and, while she isn’t always a magnetic stage presence and can seem awkward on stage, here she looked very much the angry and formidable Irish princess, and her actions conveyed her frustration and her contempt of Tristan. Elsewhere she demonstrated the importance of stillness in achieving a credible stage presence. Her diction was excellent and there were many examples of shaded phrasing accentuating critical lines. In the love potion scene, and much more so in the love scene of Act 2, she produced some meltingly soft phrasings (her singing contemplating the word ‘and’, for example), while her vocal power in extinguishing the flame and in the final moments of the love duet were astonishing. It is very difficult in listening to the ‘Liebestod’ not to bring to mind the way many others – Nilsson, Flagstad, Meier – have sung it; the powerful thing about Lise Davidsen’s performance was that it felt quite fresh – she wasn’t simply repeating how others had sung it, and she sung beautifully some parts which others have glossed over, while in turn not using the same approach as others had to other parts of the text. There was a dream-like wondering quality to her singing of the Liebestod, and this, and the sound of her glorious voice riding over the orchestra at full throttle at the climax, made for a memorable ending, and with a most beautifully floated last top note on ‘lust’ . Ms Davidsen has allowed a brief clip of the opening of the Liebestod, made presumably by the theatre staff, to be attached to her Facebook page – the link is here – https://www.facebook.com/reel/3213889715451005

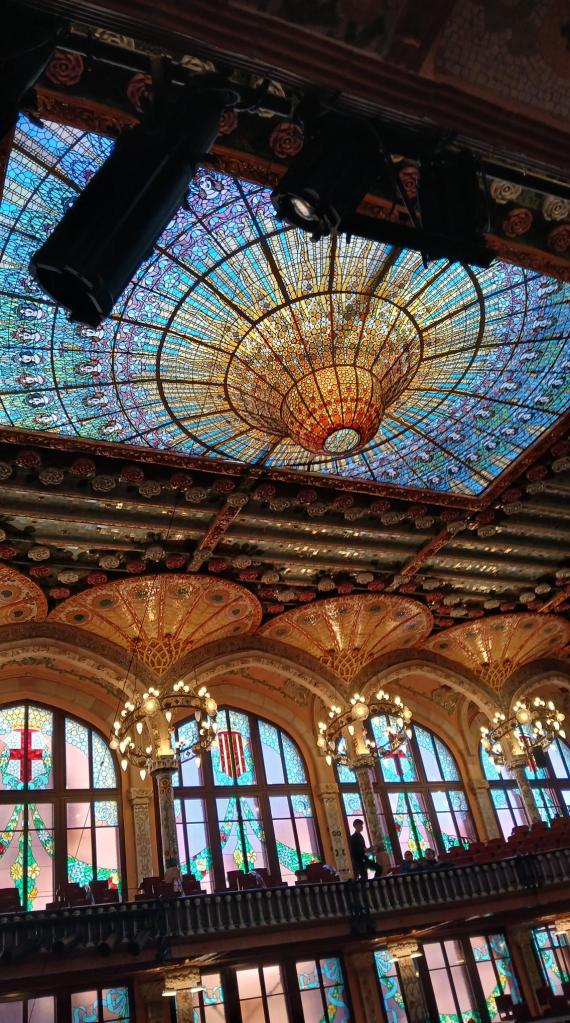

This was a starry cast and there were no weak links. Clay Hilley is one of the three or so Tristans of choice at present and you can see why. His is not a very powerful voice, but he has the stamina to still sound fresh at the end of the third act, and he delivers the text in an intelligent way, with lots of dynamic variations and colour. He doesn’t have the ardour of Andreas Schager, but, still, he is very good, and parts of his Act 3 monologues were very moving, particularly towards the end. Tomasz Konieczny as Kurwenal is luxury casting – he has been the go-to Wotan at Bayreuth for a number of years. He sung it as well as anyone I have ever heard (though I can’t now remember much about Norman Bailey in the role) and was absolutely believable as Tristan’s bluff comrade. The Brangäne, Ekaterina Gubanova, is another Bayreuth regular (she sung a very fine Kundry there two years ago which I saw). Hers is not a rich or warm voice, but her vocal style seemed admirably suited to the anxious, doubting character she was playing – even her vibrato felt part of the character. Her warnings in Act 2 were beautifully sung. And Brindley Sherratt was wonderfully sonorous as King Mark – I am sure his was the best account of the long Act 2 lament I have ever heard. I realised that the Melot, Roger Padullés, had been singing the tenor role the previous day in the Messiah at the Palau de la Musica – his Melot was as suitably thuggish as his Handel singing was bright and clear.

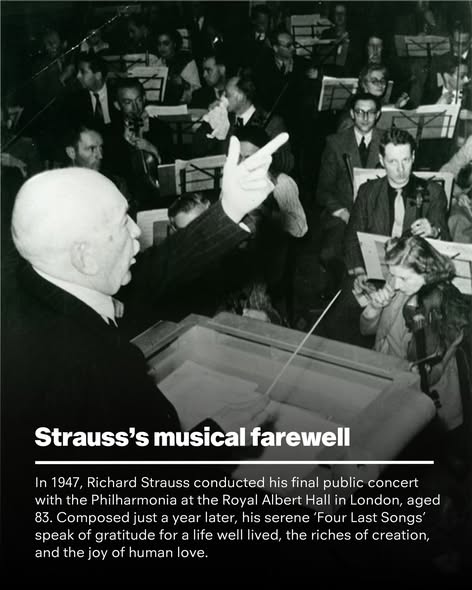

Susanna Mälkki is a name I have come across but I have never heard her conduct before, and as far as I can make out, from an admittedly cursory review of the web, she’s not had much experience of conducting Wagner in the opera house, though it looks as though she has conducted Tristan, or at least extracts of it. I was very impressed by her reading of the score, for the following reasons:

- She had clearly been working closely and well with the orchestra and they sounded very fine indeed. There were a few wobbles of ensemble in the first act but after that everything went smoothly. Some of the playing in the love duet was beyond sumptuous

- Her reading was flexible, and she was careful not to overpower the singers (which admittedly may not be possible with Ms Davidsen). Her pace at the start of the love duet was very fast, her prelude to Act 3 very slow – thus she let the emotional waves of the music ebb and flow, and didn’t impose too tight a framework, so that the audience wasn’t consciously aware that there was a directing mind behind it. Here’s a video clip of her curtain call – https://www.facebook.com/share/v/1C88vhNJyC/

I hadn’t quite appreciated in advance that – though there was an apparently fully serviceable 10 year old production in the Liceu’s repetoire, this was actually a new production – I read in a Spanish newspaper (possibly stirring it) this was because Ms Davidsen wanted her debut to be in a production directed and conducted by women. Fair enough, and the conductor choice worked out brilliantly – the directing etc less so. The production would have gladdened the hearts of those who grumble about regie-theater . There were no underlying concepts at odds with the music and text, but just a simple telling of the story, and so far so good – this worked very well. King Mark even wore a crown, and there was a love potion! However one felt at times there could have been a bit more personen-regie. The love potion scene seemed clumsily handled – Tristan and Isolde wandering around a bit aimlessly. A few times there was a standard stand-and-bark/two-singers-at-the-front set-up with all eyes on the conductor (though of course musically it was very far from barking). There was little or no set (a la New Bayreuth) – just a stage and a back-screen, and in Act 3 a kind of mirror suspended over the stage. There was some obvious light/dark contrasted lighting, as this is a basic element of the text, but oddly there seemed to be a bright light throughout the Liebestod, which seemed counter-intuitive to me – shouldn’t this be sung to gradually enclosing darkness (like Act 2, which had a lovely starry sky projected on the screen)? When the stage team came on at the end, there was a kind of growl of disapproval, and a certain amount of booing……..

Here’s a clip of all the curtain calls from the Liceu Facebook page – https://www.facebook.com/reel/821117084268049

Anyway, some production oddities aside, which didn’t matter much in the overall scheme of things, this was an outstanding performance. I am so glad I went to Barcelona to see it. Sadly I can’t see Ms Davidsen’s Met performance of Isolde screening on 21 March as I will be at Siegfried at ROHCG that night, but I am hoping to get to a Schubert song recital in late May at the Wigmore Hall