Director, Richard Jones; Set designer, Miriam Buether; Costume designer, Nicky Gillibrand; Lighting designer, Lucy Carter; Edward Gardner, conductor. Cast – Christian, Allan Clayton; Michael, Stéphane Degout; Helge, Gerald Finley; Else, Rosie Aldridge; Helena, Natalya Romaniw; Helmut. Thomas Oliemans; Grandma, Susan Bickley; Mette, Philippa Boyle; Gbatokai, Peter Brathwaite; Linda, Marta Fontanals-Simmons; Chef, Aled Hall; Lars, Julian Hubbard; Pia, Clare Presland; Grandpa, John Tomlinson; Christine, Ailish Tynan

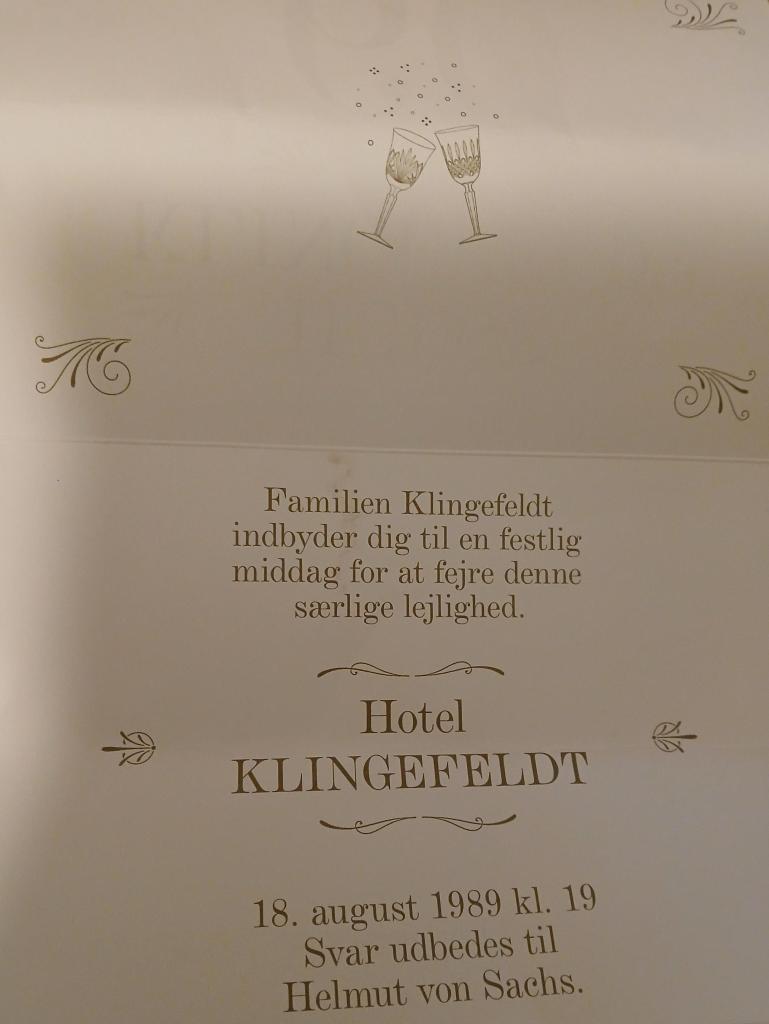

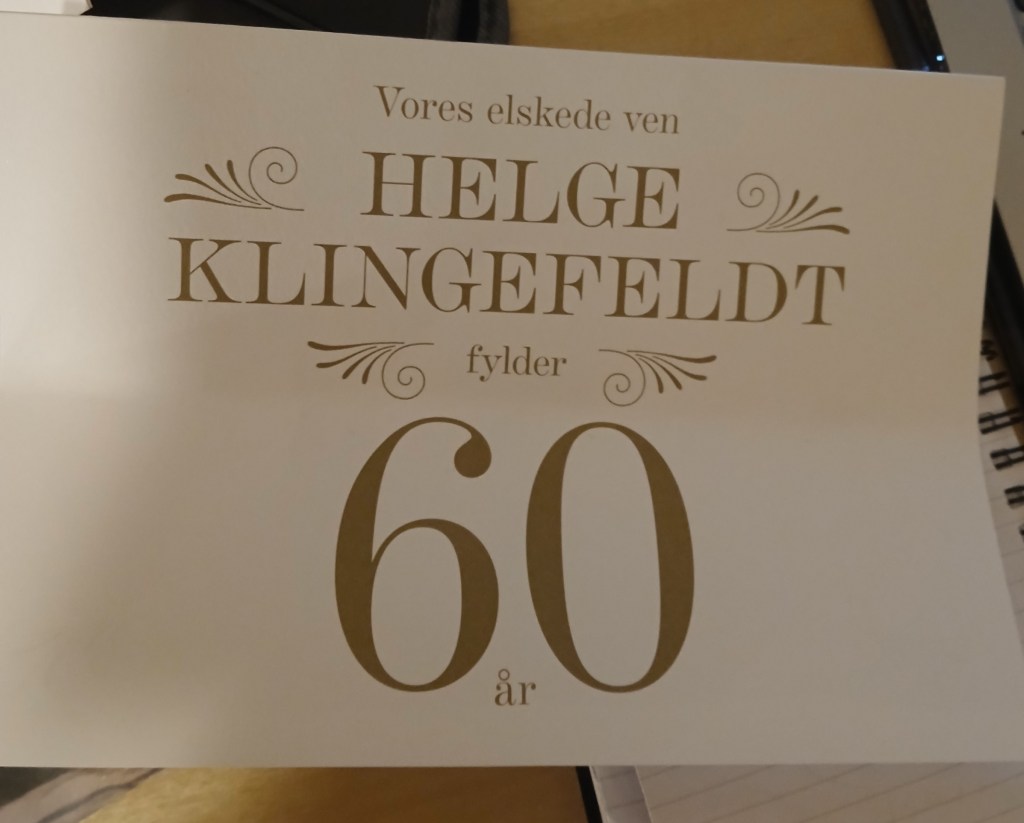

I have listened to very little of Turnage’s work – much less than I have for instance to Ades’. I have a recording of a large-scale orchestral work called Speranza, by the LSO, which I’ve found interesting and attractive but have had no encounter with his operas or other pieces. This set of first performances of Turnage’s new opera has a cast of many of the great and excellent of British singers, a very good conductor and director, and has received astonishingly positive reviews. So I went along to see this with a sense of anticipation rather than the usual feeling of dutifulness that attending new works normally involves. That sense of anticipation was shared, clearly, by many others in the audience- there was a real buzz to the pre-show conversation that you don’t often hear, a buzz strengthened by the distribution throughout the auditorium of invitation cards in Danish to Helge’s 60th birthday party, and a gaudy decoration plus a picture of Helge above the proscenium arch of the stage..

The work is relatively short – an hour and forty minutes – and without an interval. But it is one of the most intense experiences I have had in opera in a long while. The story is unsparingly grim – as mentioned, it’s Helge’s 60th birthday, and his three surviving children and spouses/partners/grandchildren all turn up with a cluster of other relatives (including Grandpa and Grandma) for a celebratory dinner in a big hotel. His other child, Linda, killed herself recently in the same hotel everyone is staying in. As his opening speech, requetyed by the toast master, , Christian recounts Helge raping his children and Helge’s wife Else being complicit in this. He continues to try to make the guests confront the truth about Helge. Not believing him, Michael – his brother – and others lock him in the wine cellar to silence him. Michael leads the guests in a song insulting Helena’s boyfriend, Gbatokai. Helena then reads aloud to the guests a letter found in the dead Linda’s room which again alludes to Helge raping the children, and that she can’t live any longer with her memories. There is consternation, and Helge has to hide in the kitchen. Michael finds him and beats him up, seemingly leaving him for dead. Guests continue to party next door while Christian thinks about his dead sister., who appears before him The coda next morning has guests arriving for breakfast, greeting each other and Helge and his wife enter – no-one alludes to the event of the previous evening and at the end Christian is left alone on stage in a slumped heap.

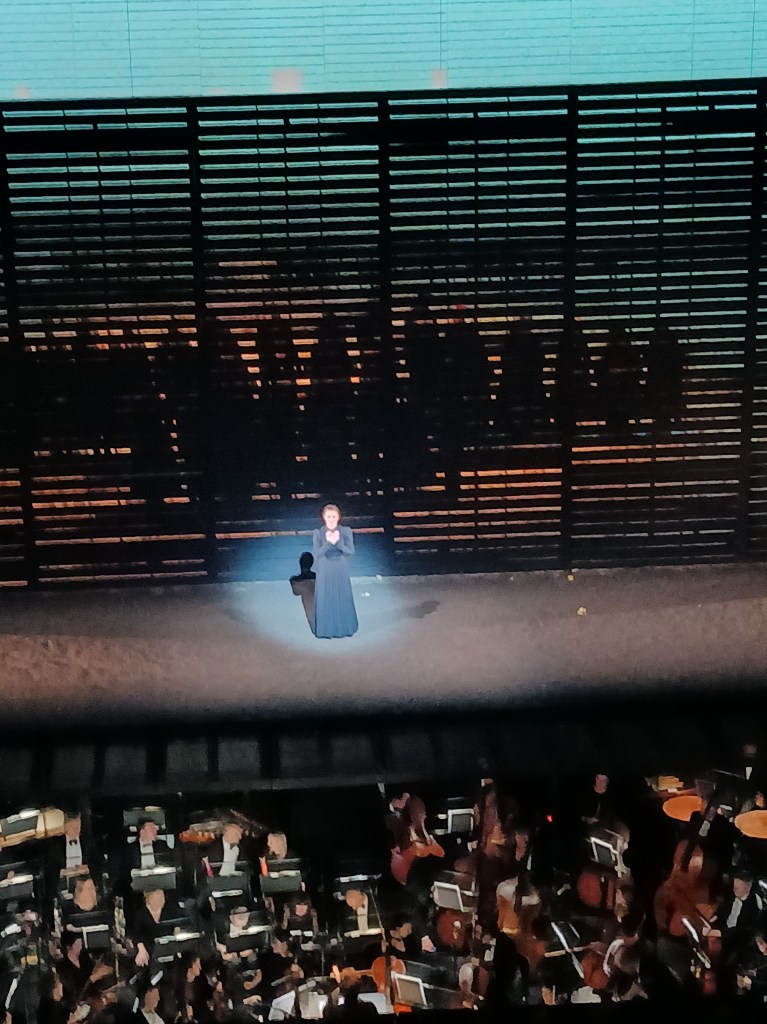

This is truly an opera – not a play with music –and the alternating moods of the music and the varied forms of singing are essential to understanding what is going on. It is one of the most impressive new operas I have ever seen on its first run. There is quite a lot of Britten about it (the ‘good morning’ chorus, the orchestral interludes – themselves reflecting Wozzeck – and the sense at the end that nothing has changed as the Village/the family goes about its business, for instance) but not in any way that is derivative – just in a way that is similarly accessible, dramatically acute and very, very moving. The musical styles are varied – there is a rumbunctious conga, some beautifully moving quiet moments for Helena and the dead Linda, passionately sad music for the last interlude as a picture of 4 children grows ever larger on a screen, some comic choruses (the one about salmon v lobster soup and the Hellos /Good mornings), some slurring jazzy moments. There is a whole world of music here. If there is one moment I cherish from tonight’s memories it is of the dead Linda singing before the last prelude the words of Julian of Norwich – ‘all shall be well and all shall be well and all manner of things shall be well’. I was in tears.

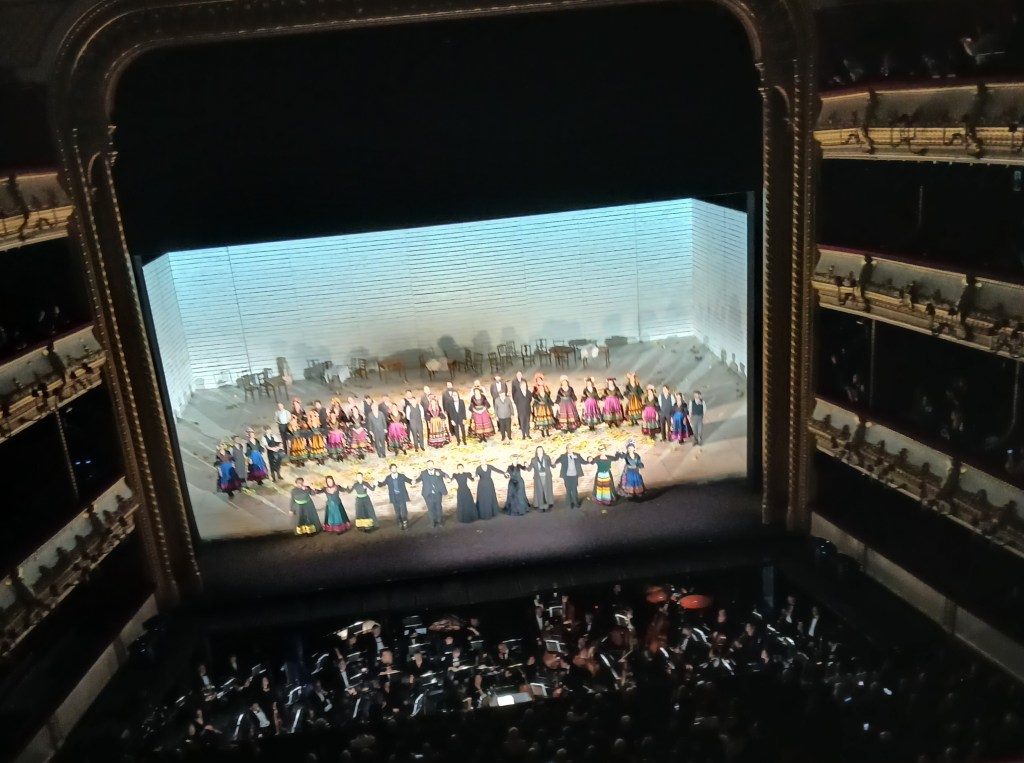

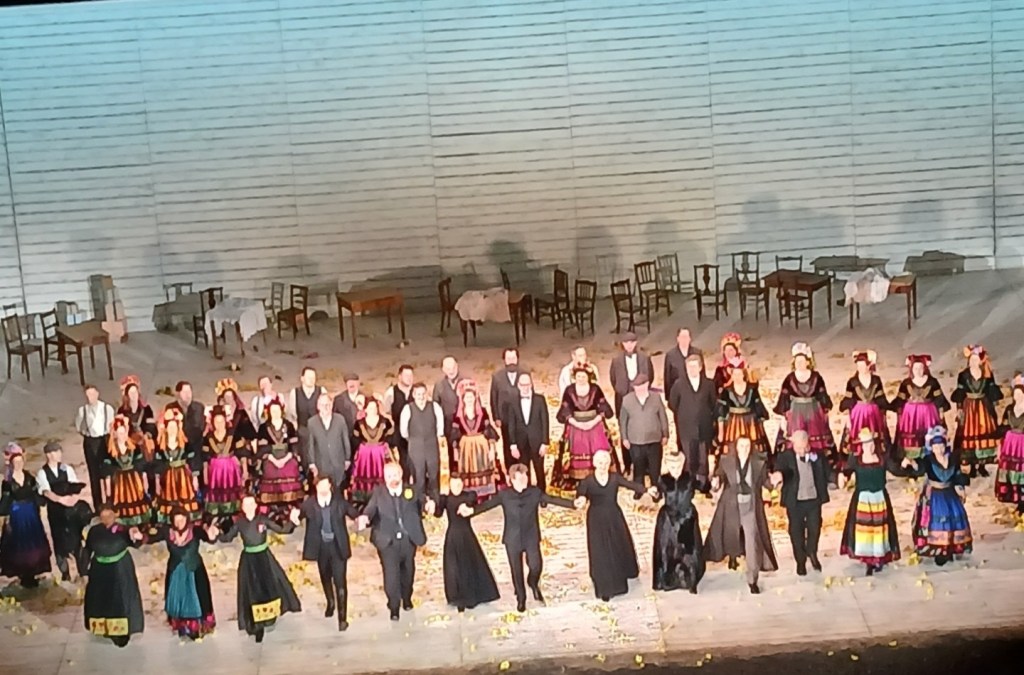

The production was very effective in moving a large chorus and a very large cast deftly around the stage. The chorus of family members was well characterised so that each seemed an individual, and there was little that looked artificial in the way they moved. The hotel reception area as in the photo doubled as the main dining area for speeches; there was then via dropped screens a split stage area appearing for scenes with individual characters and groupings . Richard Jones I always find to be effective but this must be one of his best shows.

The super-star cast were all splendid – Allan Clayton excelling as Christian, Natalia Romaniw outstanding as Helena, Gerard Finlay smooth as Helge, Stéphane Degout a strong stage presence as Michael and John Tomlinson having the time of his life as Grandpa. And Ed Gardiner kept the orchestra taut and thrilling. This must be one of the very finest new operas of the last 25 years. It will surely have multiple productions in Europe and the US. I was very happy to see Turnage appear on stage at the end (see photo, with his trademark silly hat), hugely cheered by the packed) audience. I was amused to read that a few critics felt the music was too easy-on-the-ear and insufficiently ‘gritty’. What planet do these guys live on?