Anthony Marwood violin; Coleman Itzkoff cello; Aleksandar Madžar piano. Shostakovich, Violin Sonata Op. 134; Tchaikovsky, Piano Trio in A minor Op. 50

As i travelled to London for an evening Wigmore Hall concert, prior to moving on the next day to Paris, I found myself thinking about the dire state of British politics. In front of me on the train, having a rare old time, were three young men who I took to be Christian nationalists, who seemed to be reading and listening to a heady succession of lectures and podcasts about England becoming a Godly Kingdom and properly Christian again, the end of the domination by other religions, particularly Islam, a new era of Christian colonialism and victory over other nations. There was a very creepy-sounding South African ideologue speaking, chunks of Ezekiel, and also some references to the ‘Young Lions’, an Assemblies of God group, I believe, as well as ‘Tarshish’, which apparently in end-times conversation means a group of nations who will stand against the Anti-Christ . Of course, I should have engaged them in conversation but, in the usual British way, didn’t and just buried my head in my computer. Suddenly, not entirely relevantly to the young British Christian nationalists but entirely appropriate to Shostakovich’s violin sonata, there came into my head Edgar’s lines from King Lear – “The weight of this sad time we must obey; Speak what we feel, not what we ought to say” (or in my case, speak what will be socially embarrassing because it’s important to speak up, not just keep silent out of politeness …..)

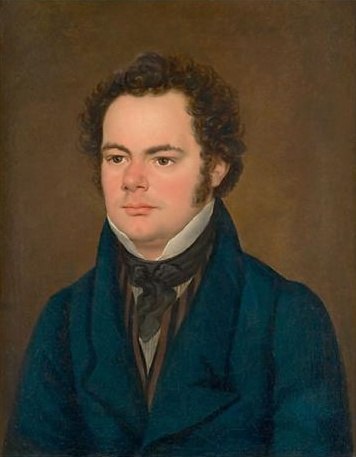

Shostakovich by the late 60’s though WAS able to speak through music what he felt, and in no way held himself bound by what Soviet orthodoxy said he ought to say. The Violin Sonata is not as bleak as the later Viola Sonata but it is by no means easy listening – using elements of 12-tone practice, deliberately spare and not easily relatable melodic material, and clearly focusing on Shostakovich’s increasingly frail health and serving as a meditation on death and dissolution. I find I just have to submit to it and accept its slow, fragmentary movement – there are moments of grim humour but no revelation, just, at the end, a gradual dying away. It is a moving experience, and was beautifully and sensitively played by Anthony Marwood and Aleksandar Madžar. It’s never going to be one of my top ten musical experiences of the year, but it is very rewarding nonetheless.

I don’t know to what extent this well-known British violinist and, from my perspective, less well known Serbian pianist and American cellist often perform together, but there was a definite rapport and sense of common understanding between the three players in something of a barn-storming performance of the Tchaikovsky Trio. It’s a work I’ve heard live once before, performed in Sheffield by Ensemble 360 and I was rather bowled over by it at the time, particularly its ‘big tune’ that opens and closes the work, and bought a recording of the work as a result. Listening to it again, I was more conscious that it is a long work – coming up to 50 minutes in this performance – and one which sometimes meanders a bit, particularly in the Theme and Variations section, where there was a sense of ‘”…and next…, and then…….”. Apart from the ‘big tune’’s return, I didn’t get much of a sense of structure in the work – it sprawls, rather. But it’s always appealing, doesn’t seem to go in for noisy rhetorical gestures, the grand moments of the work came off well, and this was a performance of utter conviction and passion, I felt. There were lots of audience whoops and cheers at the end, well-deserved. Was Tchaikovsky really saying what he felt, though, rathe than what he ought to say to the bourgeois salons of St Petersburg and Moscow? I’m not sure……………………