Conductor, Pablo Heras-Casado; Director, Jay Scheib; Stage design, Mimi Lien; Costumes, Meentje Nielsen; Lighting, Rainer Casper; Video, Joshua Higgason. Amfortas, Derek Welton; Titurel, Tobias Kehre; Gurnemanz, Georg Zeppenfeld; Parsifal, Andreas Schager; Klingsor, Jordan Shanahan; Kundry, Ekaterina Gubanova

After a, by now almost normal, rather chaotic performance by DB I arrived in Bayreuth last night only an hour or so later than I had planned – my train to Frankfurt was late by 30 mins but then so was the train to Nuremberg!) So now, in extreme heat, I am in Bayreuth for 3 days to hear Parsifal, Tristan and Tannhauser. The Festspielhaus shimmered in the distance as I approached it, and most men had their jackets off.

I went to the previous Parsifal production when in Bayreuth in 2017 with some of the same personnel – Schager, Zeppenfeld and Welton – and thought it very effective, though musically quite fast (Haenchen).I saw video clips from this current Parsifal when it was a new production last year, and thought it, from the extracts I saw and heard, both musically well-led by Heras-Casado and an interesting production which, whatever its quirks, did not deviate too radically from the settings and context laid out by Wagner, and warranted a closer look – all the fuss about the special augmented reality glasses being a bit beside the point for all but a minority of the audience. There were hostile critical reviews, though – the Financial Times was particularly upset: “None of the fundamental questions (who are these knights? What kind of society have they created? Who is Kundry? What is the Grail? What is redemption?) are addressed” in the production. So it’s as good a way as any of starting this review by seeing how I responded to those questions, having experienced the production live.

There are two preliminary point to be made about the production. The first is that, unlike some regietheater productions this is pretty faithful on the whole to Wagner’s stage directions – if Wagner says there are fallen heroes in Act 2, there they are, gruesomely beheaded; there is a grail and a spear, and a full set of ritual accompaniments – various bowls and relic-holders, plus a full acted out reception of the Grail, with processions; though the setting of Act 3 Scene 1 is very far from a sunny Good Friday woodland, some flowers are brought in for the Good Friday music. These are just a few of many examples. The second is the extensive use of a live video-cameraman on stage, throughout nearly all of Act 2 and large portions of Acts 1 and 3, the video being then shown live on the huge back wall of the stage. Clearly there are points here the director wants to make, which we’ll come onto, but it is a very effective way of enlivening long relatively static scenes such as the encounter of Kundry and Parsifal in Act 2.

So….what of the Financial Times’ questions. It’s a mixed bag, I think. The society portrayed in Act 1 is a technological one – the setting is almost like some sort of quarry, with bright steel poles and a monstrous gleaming steel-sided Tower of Sauron affair, which flashes like a light-house during the Grail scene. The poles crackle when Kundry first approaches. The Grail Knights are military in appearance – large men, shaven heads – and wear camouflage uniforms. The latter may indicate that they are unable to show their true feelings to each other – life is transactional. Or it may be that they are people evading reality The extensive (maybe half of Act 1 Scene 1) filming of the repeated bandaging of the oozing blood from Amfortas’ wound shows they have compassion in terms of what to do with wounded bodies (or a wounded swan, who gets the same treatment) but not in relation to wounded minds. The reference to wounded minds here mainly relates to Kundry, who is much more centre stage throughout the work than is usual – she is there through the first grail scene – but it also refers to Gurnemanz: the prelude to Act 1 has a videoed encounter he has with a young woman in a dream sequence, who he is obviously deeply disturbed by. She appears at moments throughout the opera in a white gown – she is in the Grail Scene and she arrives as some sort of page to Parsifal in Act 3 scene 1 and remains on stage for the rest of the performance. So it’s fair to say that the knights have a problem with women (in particular no-one understands or can sympathise with Kundry) and that religious ritual is more important to them than real relationships……….Maybe also the video cameraman (who is dressed in military camouflage) is suggesting through the videoing something about people seeing themselves through social media and selfies rather than through the mirror of human relations. A pool of water is there in all three acts in the sets, perhaps representing a more honest way of life and the power to transform.

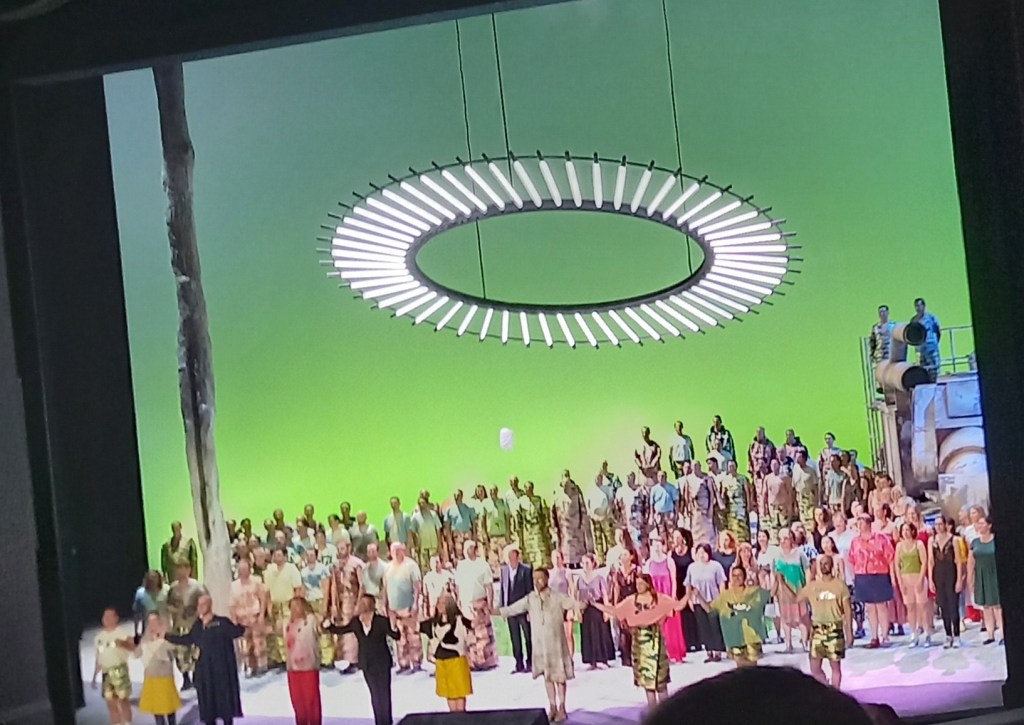

Act 3 shows a society that has undergone climate catastrophe – a stagnant green pool (perhaps an image for the knights themselves) in Act 3 Scene 2, though still alive for the baptism in scene 1)l there is a rusty piece of machinery in the quarry. Everything seems dead. The woman Gurnemanz saw in his dream brings on the flowers for the Good Friday music

So far so good-ish. Where the problems come is in trying to see what ‘redemption’ means in this context. The director’s answer to this is to have Parsifal, once he has reunited spear and Grail, is to smash the Grail (which is a large maybe hexagonal stone – fair enough since this is how it is described in some of the sources). He and Kundry then wade into the pool and raise their hand towards the gas ring object that floats above it/the temple, maybe in recognition of something ‘above’ beyond religious ritual. Tentatively, Gurnemanz and the other woman also come together and acknowledge each other. So by this is the director saying that redemption is about restoring ambulant heterosexual relationships and (as one of the directorial team puts it in the programme ‘trying to be a bit friendlier with each other’)? This does not sound like a full understanding of the word redemption to me, and the director really doesn’t really get to grips with the religious element of the work – religion is not necessarily just about being nice to each other, though it should include that. It’s significant that the point of the text of the Good Friday music felt mainly ignored in this production. So much could have been done with ‘Entsuendigte Natur’ in a climate catastrophe context.

What’s good about the production is the increased focus on Kundry, on her humanity, on her being someone definitely different by the end. The crux of understanding her is in Act 2, and here also there was to me some confusion, perhaps inintended but brought to my mind by the fantastic performance of Elena Gubanova and the close up images from the video – so real does Kundry’s passion become that I lost the sense that she is doing what she does in Act 2 under a spell; it seemed to come from a genuine part of her nature. How then she becomes the penitent figure of Act 3 is then unclear. Meanwhile in Act 2 Parsifal’s T shirt has ‘ Remember Me’ on its back. Is this about Amfortas, or the rather solipsistic world Parsifal is still in? Again, apart from being naturally instinctive and not camouflaging his feelings, it is a bit difficult to understand Parsifal’s journey in this production

These comments are inevitably a bit unfocused, scribbled down during and after the performance, but I hope you can see something of the merits and problems of this production – the major defect being to remove it from the sphere of religion and what we might mean by ‘redemption’ in a modern context. The major achievement of the production is the way it focuses on the journey made by Kundry. One other thing to highlight is, as ever with Bayreuth, just how spectacular and colourful the sets and costumes are – they are extraordinarily good

Musically this performance was wonderful. The five major roles all performed magnificently – Zeepenfield (maybe his voice a bit drier than when I heard him last in this role 7 years ago) articulated the words clearly and sang sensitively; Derek Welton has a marvellous voice and deployed it well; Jordan Shanahan was maybe less distinctive than others but did all that was required of him as Klingsor; Ekaterina Gubanova was (as I think the director intended) the star of the show, and I have never heard Act 2 sung better or been more gripping (eclipsing even the version given by Opera North a couple of years ago); Andreas Schager does what he does with all his heart and soul – I have never heard ‘Amfortas, die Wunde’ more strikingly sung on stage – and quite often with sensitivity too. You can’t but worry though about the amount he takes on at Bayreuth and in fact he was off last week with an infection. We’ll see how he gets on in Tristan tomorrow. There were some signs of wear and tear on his voice. Heras-Casado I was as impressed by as I was listening to last year’s performance on video – flexible, always bringing climaxes to a full conclusion, moving the music along but with sensitivity. He was full-throatedly cheered and stamped for by the audience at the end, as were all the singers except for the poor Flower Maidens for whom there was some silly and quite unjustified boo-ing in the worst Bayreuth fashion. There were a few over-the-top people around in the audience, including the chap in front of me who upbraided the Mum of a teenage daughter in front of him for the girl’s fiddling with her phone during Act 1 (I think the poor girl was just trying to follow the plot), muttering ‘Unmoeglich’ several times.

On to Tristan tomorrow