Erkki-Sven Tüür, Aditus; Beethoven Piano Concerto No. 5 in E flat major, ‘Emperor’; Bruckner Symphony No. 1 in C minor (1877 Linz version, ed. Nowak) Yunchan Lim piano, BBC Symphony Orchestra, Paavo Järvi conductor

I am trying, in my intensive July and August live concert listening, to pay particular attention to works I have scarcely ever heard – Prokofiev and Weinberg operas in Salzburg, the concert I reviewed last week at the Proms (Schoenberg and Zemlinsky), Ma Vlast (apart from Vltava I have never heard any of this), and Suk’s Asrael Symphony at the end of August, the Handel opera in Buxton – and this concert. Apart from Florence and The Machine, this was one of the first Proms to sell out. Initially I wondered why – Bruckner 1, which I have never heard live before, I was looking forward to hearing but it is scarcely a crowd-pleaser. And the Emperor concerto crops up all the time. Paavo Jarvi is undoubtedly a fine conductor, but he’s a fairly regularly visitor to the UK, and to the Proms. Then I realised that the big deal was Yunchan Lim, who is a 20-year-old South Korean pianist. At 18, he was the youngest pianist ever to win the prestigious Van Cliburn International piano competition in Texas, and he is now regularly referred to in the classical music press in hyperbolic terms (‘the most exciting pianist on the planet’, ‘Yunchan Lim’s playing is so good you think you’re dreaming’; ‘Is this 20-year-old the greatest pianist of our times? ; Yunchan Lim, the Korean about to electrify the Proms’ (The Guardian) etc). So I wondered how I would find his playing….

The house was, as indicated above, packed. First up though in the programme was a short work by Erkki-Sven Tüür (not a name I have come across before, a 64-year-old Estonian composer, who ran a rock band at one point in the 80’s). The work performed, ‘Aditus’, was in memory of his teacher Lepo Sumera (8 May 1950 – 2 June 2000) who was an Estonian composer and teacher. An ‘Aditus’ is the opening to some interior space or cavity. This first work seemed to consist of a series of vortices – a strong statement followed by a gradual dissolution of sound. There were maybe 4 or 5 such attempts, including a much faster rhythmic section, all eventually ending in silence. It did not, at 9 minutes or so, outstay its welcome and I shall listen to it again on I Player.

Mr Lim is a diminutive figure who barely looks at the audience and seems utterly wrapped up in his playing. His playing of the Emperor concerto, as you would imagine, was immaculate technically. That sounds as though it is to be followed by a ‘But’ but it won’t be. There were wonderful poetic moments of feathery lightness; phrases lovingly sculpted. Many passages I felt I was hearing for the first time, particularly in the second and third movements and these two were probably the best elements of his reading. He also had magnificent support from the orchestra and Jaarvi who offered a propulsive performance, full of energy, nice pointing and bounce, with a hard stick timpanist adding to the excitement. What I did feel is some distance between what the orchestra was doing and the vision of the pianist – his playing suggested a more Schubert, maybe Schumann, – like grace, lyricism and melancholy that just didn’t seem to gel with the more robust approach of the orchestra. Of course the Albert Hall sonic experience can always be a factor but this was certainly not sounding to me like a barnstorming performance, and I thought maybe Lim might have needed maybe more time with Jaarvi to establish a common approach. Lim played beautifully a Bach transcription by Wilhem Kempff as an encore.

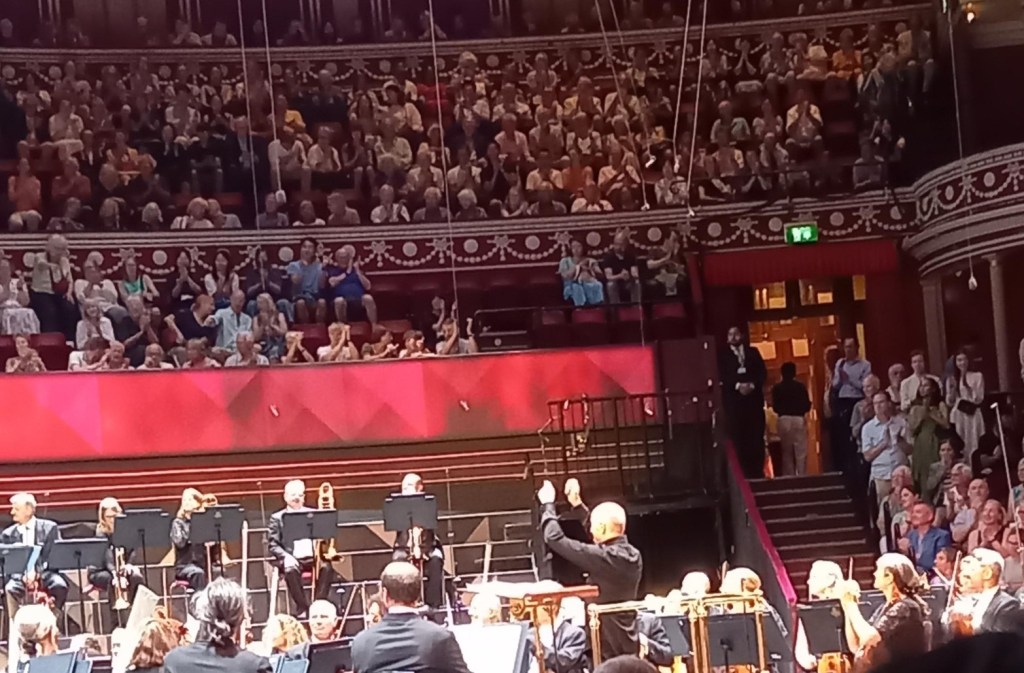

There were significant numbers of Koreans in the audience out to support the young pianist in the first half and it was great that nearly all of the packed Albert Hall audience returned for the Bruckner in the second half. The Bruckner symphony is in some ways a tentative piece from a famously late-starting composer- he was 44 when he wrote it- but nevertheless many of the characteristics of the later symphonies are there: the enormous full-stops-out brass passages followed by silence, the quirky woodwind inner voices, the folksiness in the Scherzo, the obsessive repetitions of phrases, the slow movement climax. What’s perhaps surprisingly not there so much is memorable melodic material in some movements. The Scherzo is the section most closely aligned with those of the later works, and the most memorable – a thumping tune, exciting brass and building to thrilling climaxes. The first movement starts with a trudging Schubert-like melody and follows the mature Bruckner pattern of having three subjects. I didn’t find it easy to follow the flow of the argument of the development section but it has an exciting ending! The slow movement is slightly different to those that follow it in the later symphonies. Perhaps influenced by the previous, on the whole, gloomy first movement it starts in disarray – phrases that fall in on themselves, sounding as though they are about to break into song and then collapsing. The main theme enters tentatively – perhaps a gradually emerging faith – and gradually builds up to a thrilling climax and beautiful calm coda. The finale, as often with Bruckner, sounded to me the weakest movement, with a repeated 5 note motif thumped out, rather undistinguished melodically second and third subjects, lots of brass and a major key ending which is glorious.

I haven’t heard much of the BBC Symphony Orchestra in recent years and when I do I am always perhaps unfairly surprised by how good they are. In particular the trumpets blared out with utter precision, there were some beautiful woodwind solos (bassoon particularly distinguished) and the strings in the slow movement glowed richly. Jaarvi pushed the music along at quite a pace, which I think is right with this work – it’s not one for Celibidache-like luxuriating.

All in all this was a deeply satisfying evening!