Conductor: Christian Thielemann; Director, David Bösch; Stage design Patrick Bannwart; Costumes Moana Stemberger; Lighting Fabio Antoci; The Emperor Eric Cutler; Empress, Camilla Nylund; The Nurse, Evelyn Herlitzius; The ghost messenger, Andreas Bauer Kanabas; A Guardian of the Threshold of the Temple, Nikola Hillebrand; Apparition of a Young Man, Martin Mitterrutzner; The Voice of the Falcon, Lea-ann Dunbar; A voice from above: Christa Mayer; Barak, Oleksandr Pushniak; Barak’s wife, Miina-Liisa Värelä

I have only ever seen Die Frau ohne Schatten in one production, and that almost 50 years ago. I saw it conducted in 1975 by Solti at ROHCG, with James King as the Emperor, Heather Harper as the Empress, Helga Dernesch as Barak’s Wife, and Donald McIntyre as Barak, and then again in 1976 with almost the same cast but with Walter Berry as Barak. Both were wonderful performances that have remained vividly in my memory.

The thirty one year old Fritz Reiner conducted the second ever performance run of Die Frau at the Semperoper in 1919 so there is a real sense of history in a performance of this work here in Dresden.

This was the first night of a new production, so there was nothing in the way of easily accessible press commentary to find out what line the director might take – and this being the sort of work it is, I would imagine it is a veritable playground for directors to carve meaning out of what is sometimes a confusing symbolically-overloaded plot. It was a great merit of the production that it focused on good story-telling and (just like the Magic Flute) offering a box of magic tricks – it was surprising, in this, the land of regie-theater, to find a clear focus in a production on narrative, and letting the music and words sort out the meanings for themselves. Although I know the music fairly well, I had been wondering what it would be like to see this on stage after so long – would I think it simply a rather silly work with lots of glorious music. In fact, I think that, despite the portentous supernatural trappings, it is a moving work, a profound work, and I was utterly gripped by it from start to finish, and this was a very good production of it.

For starters it is both exciting and extraordinarily tuneful musically – it must surely have a claim to be Strauss’ greatest work (that would certainly be my view). The orchestra is huge – Wikipedia claims 164 instruments are involved (not players of course): the percussion section includes glass harmonica, 4 timpani, 5 Chinese gongs, cymbals, snare drum, rute, sleigh bells, bass drum, tenor drum, big field drum, triangle, tambourine, 2 castanets, tamtam, whip (slapstick), xylophone, glockenspiel, 2 celestas). The beautiful string upswelling in the orchestra telling of Barak’s affection for his wife in Act 1 was magical, with Thielemann bringing out more passion from the strings than you would have thought possible at the climax of that passage. The duet expressing absence and abandonment by Barak and his wife at the beginning of Act 3 is one of Strauss’ finest creations. The Nightwatchmens’ chorus at the end of Act 1 is wonderfully moving. The Emperor’s soliloquy in Act 2 with its marvellous solo ‘cello part was another lovely piece of writing. The final sequences of orchestral blaze in the last 10 minutes of Act 3 during transitions between scenes are some of the most exciting pieces of music I know, and the orchestra sounded quite glorious playing them on this occasion – Thielemann seems to have an unerring sense of when to let the orchestra rip to maximum effect. The music of the falcon is among the bleakest and most melancholy I know, while the ‘Water of Life’ music is fascinating, very ambiguous, giving a sense both of beauty and danger. The solo violin music just after the Empress refuses the Water of Life was beautiful – and wonderfully played (though marred by an almighty crash caused by some hidden piece of scenery going into destruct-mode). I wish I could have gone to another one or two performances of this run – it’s such a wonderful work.

The production had two basic points of reference – the spirit world, with white gauze curtains closing off parts of the stage, and a very down to earth Barak’s kitchen / living room, with wedding portraits on the walls and some splendid dying vats and a washing machine, as well as a couch and a bed. Behind them both is a screen onto which can be projected videos – e.g. fishes for the frying fish sequence and the attractive young men summoned up by the Nurse for the Dyer’s Wife (why doesn’t she have a name?), while in the spirit world there are falcons, gazelles, feathers and human images – but many more as well . There are also some objects/prop, sometimes tongue in cheek where the spirit world is concerned – the Messenger of Keikobad has a cigarette before a ‘difficult conversation’ with the Empress, and there is a rather dodgy lift which moves between the spirit world and the human world. There is also what could be a comic but in fact is terrifying, puppet falcon, huge, with a wingspan extending across the stage, with blazing lights for eyes, who carries in Act 3 the almost-stone body of the Emperor. There’s plenty of dry ice and on occasion individuals or couples are swallowed up by sudden gaps in the stage. Barak’s house splits into two at the end of Act 2. The passage where The Dyer’s Wife is being sold a life of untold luxury was brilliantly done in Act 1. Dresses came down on hooks from the flies alongside elegant young women in approx. ?1920’s Party gowns. But there is no real sense of any alternative reading here – just lots of inventive detail. The only real production ‘alternative reading’ was at the end. The last scene moves from the spirit world to Barak’s house and both couples now appear in ‘human ‘ clothing to sing the final pages. As the unborn children start singing, after the last orchestral climax, Barak’s house splits apart – in fact with Barak and the Empress on one side and the Emperor and the Dyer’s Wife on the other. The void between the two split parts of Barak’s house contains the Nurse who remains there until the end of the piece looking enigmatic and staring out at the audience. I thought it could mean several things – that peril, and difficulties, and ‘negative experiences’ don’t just stop when you have children; or could it mean that there will be some people who are just not interested in having children and find their fulfilment in other ways. Either way, it’s a perfectly reasonable way to stage the ending.

Costumes are varied – possibly 1920’s/30’s for Barak and his wife, white cool dresses and suits for the imperial couple, and a cloak for the Nurse.

What’s it all about? The good thing about this production is that you didn’t need to worry about that – here were two couples with a rather nasty manipulative individual messing with their heads, but all comes out right in the end. That, and some stage magic, was all that was needed to get into the story. But the other reason the opera works is because the characters and what they say and do are deeply believable. Barak is a big, maybe slightly slow, man with simple, strong views; the Dyer’s wife (here with a cigarette never far from her mouth, sharp-tongued, conflicted and also vulnerable); the Empress – privileged but empathetic and in love with her husband; the Nurse, bitter, sarcastic, dismissive – a strong malevolent presence – and the Emperor, more of a cypher than the others, perhaps, but in love with his wife. One thing for sure – someone, whether Hofmannsthal or Strauss, writing this has had a difficult relationship to deal with – the work is a very deeply realistic picture of how poorly men and women can behave – it’s profoundly painful. And that’s what makes it a great opera – its truthful depiction of human emotions and, in the context of 1919, a profound hope for the future represented by the unborn children and all the hope that’s in them. True, there are also time-specific views about how male/female relationships work, and it’s hardly into diversity – but there is enough in the opera that goes beyond passing cultural norms to express something unchanging in human nature that will always be relevant.

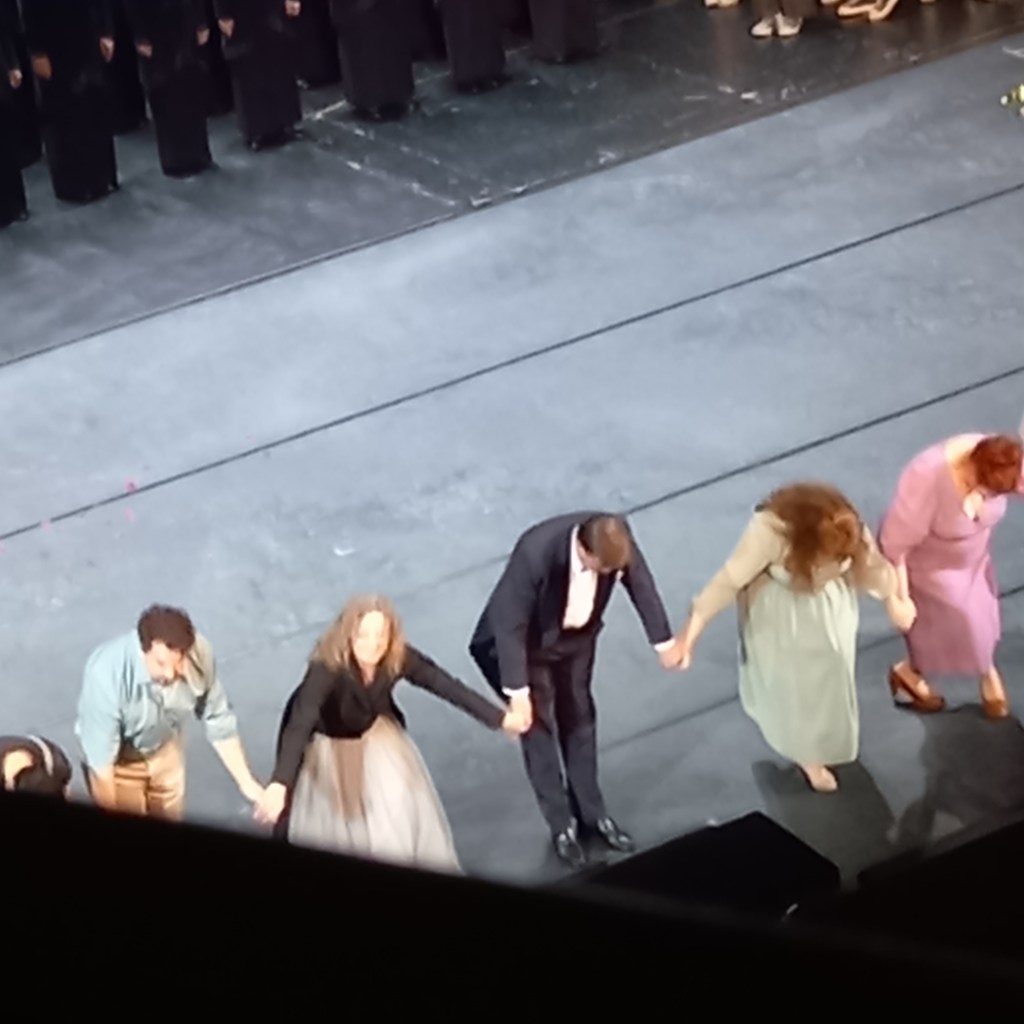

The Semperoper cast list had some people in it whose names I hadn’t come across before – e.g. the man playing Barak – but also a number of well-known singers – Camilla Nylund, performing in the Tristan I’m seeing at Bayreuth this summer, and Miina-Liisa Värelä who I heard singing Isolde in the Glyndebourne Proms Tristan performance nearly 3 years ago. There were three complete triumphs in the 5 major roles and 2 very good performances – which may have something to do with the way Strauss and Hofmannsthal characterised them. Both for her singing ability and her acting the star performer for me was Miina-Liisa Värelä, who gave a moving account of this character in all her contrariness, her affection and yet irritation with her husband, and sang it fantastically well. Barak was another singer absolutely absorbed in his role, looking every inch the part and shambling his way round the kitchen, and with a warm, rich voice. The Nurse has a lot to do, and sing, and Evelyn Herlitzius was tireless, physically and vocally, performing this character, with great diction and strong projection. I found Camilla Mylund’s voice a bit on the small side for the Empress, but she sang well – beautifully so in Act 3. Her encounter with her father was gripping. Arguably the Emperor doesn’t have that much to do – the usual thankless Strauss tenor role – but he has the power and presence to do what’s needed.

Thielemann and the orchestra were just overwhelming – no other words……………….

A great evening!!

R. Strauss 1918